The Revolutionary Story Of Laurent Ferrier’s First Watch: A Tourbillon With Two Hairsprings

Technical

The Revolutionary Story Of Laurent Ferrier’s First Watch: A Tourbillon With Two Hairsprings

Summary

Language is a funny thing. As a native English speaker, I often squirm at the Swiss watch industry’s apparent fondness for the words “disruptive” and “audacious”. A feature of many press releases, these words make me think of alcohol-fuelled loutishness and an unbecoming degree of impudence, respectively. And yet, surprisingly, the word “audacious” does seem appropriate when discussing the Laurent Ferrier Classic Tourbillon Double Hairspring. Allow me to elaborate.

Laurent Ferrier Classic Double Spiral Tourbillon is an ambitious undertaking

Back in 2010, the newly formed Maison unveiled its inaugural watch, the Classic Tourbillon Double Hairspring. This timepiece, despite its clean, elegant and simple dial design, was imbued with a remarkably complex and ambitious movement, the Calibre LF619.01.

Most brands tend to play it safe with their early offerings, adhering to a “walk before you can run” policy. Nevertheless, unlike most watch brands, Laurent Ferrier has always followed its own path to horological greatness. Indeed, from the outset, Laurent Ferrier demonstrated a level of boldness seldom seen with fledgling firms, creating a watch that immediately rivalled the work of watchmaking’s old guard. In this context, the word “audacious” seems very appropriate.

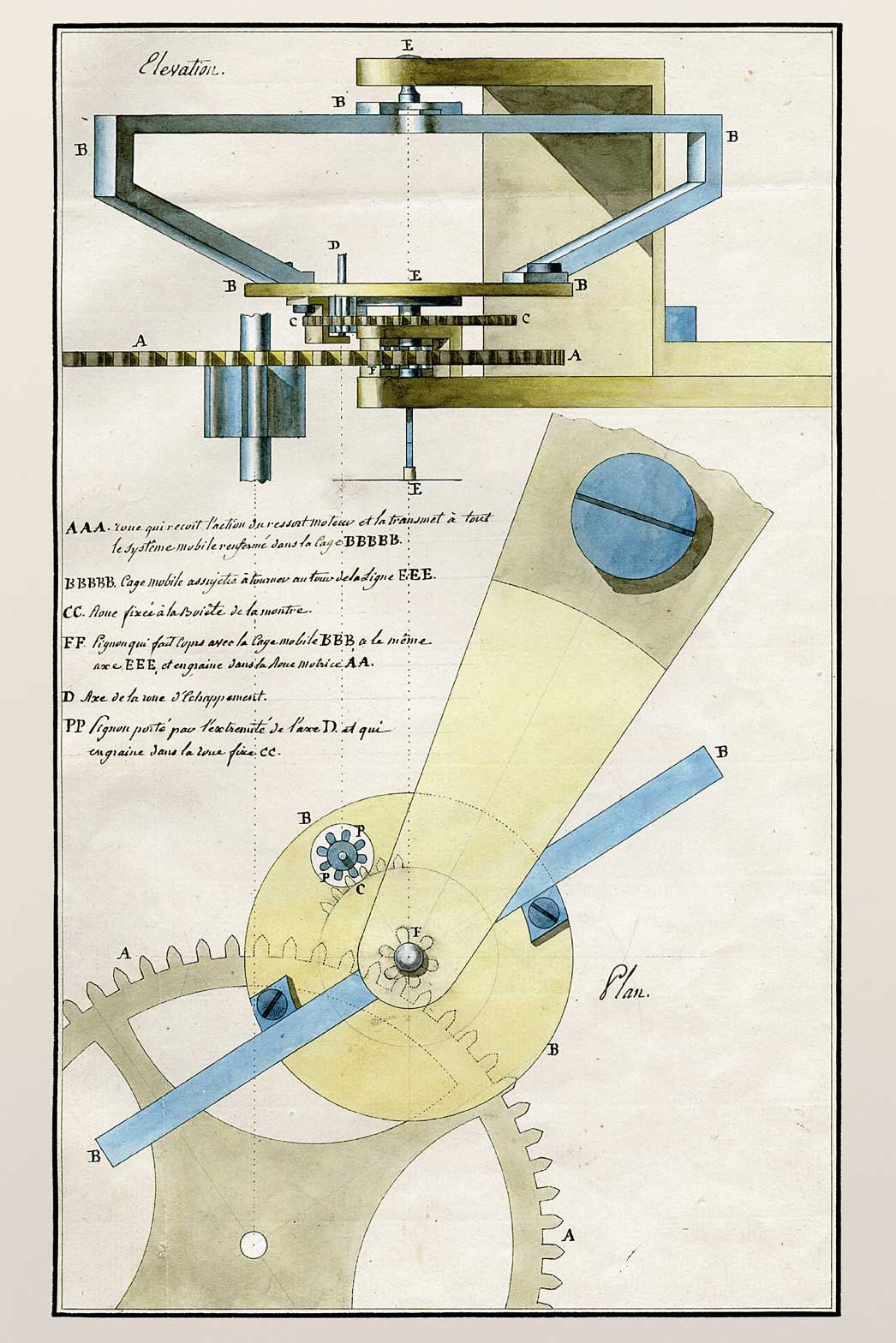

The tourbillon, as most horophiles will already know, counters the adverse effect of gravity on the regularity of a movement. It was the brainchild of Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823) and was patented in 1801.

On June 26, 1801, in France, Abraham-Louis Breguet earned the rights for a patent which would last for a ten year period for a new type of regulator called the “Tourbillon” (Image: breguet.com)

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s very first four-minute tourbillon and his third tourbillon watch ever made, best known as the no°1176, the timepiece is an 18K gold openface pocket chronometer with four minute tourbillon, échappement naturel, double subsidiary seconds, power reserve, stop-seconds feature and gold regulator dial; signed Breguet et Fils, No. 1176, case no. 1282, sold to Comte Potocki through Monsieur Moreau in St. Petersburg on 12 February 1809 for the sum of 4,600 Francs (Image: breguet.com)

By placing the escapement and regulating organ in a cage that rotates 360° every 60 seconds, the unwanted influence of gravity is ameliorated. The finest tourbillons draw on the talents of the most accomplished watchmakers, individuals who practise their craft with deft use of hand and an inordinate amount of amassed knowledge.

Notwithstanding that a tourbillon is a formidable undertaking, Laurent Ferrier reimagined the high complication, adding an additional layer of complexity, a double hairspring. But what is the benefit of equipping a movement with two hairsprings? Well, before I can answer this question, we need to go back to school.

From pendulum clocks to hairsprings: Solving precision problems in watchmaking

(1564-1642), a son of Florence, discovered that a pendulum is isochronous providing it swings in a cycloid curve. He observed that as the pendulum swung, its amplitude had no influence on the duration of the oscillation. Recognizing the potential of a pendulum as a precise mechanical oscillator, he began work on a pendulum clock in 1637 but passed away before completing it.

- Galileo Galilei, 1564-1642 (Image: Justus Sustermans)

- Dutch mathematician, physicist and astronomer Christian Huygens (1629–1695)

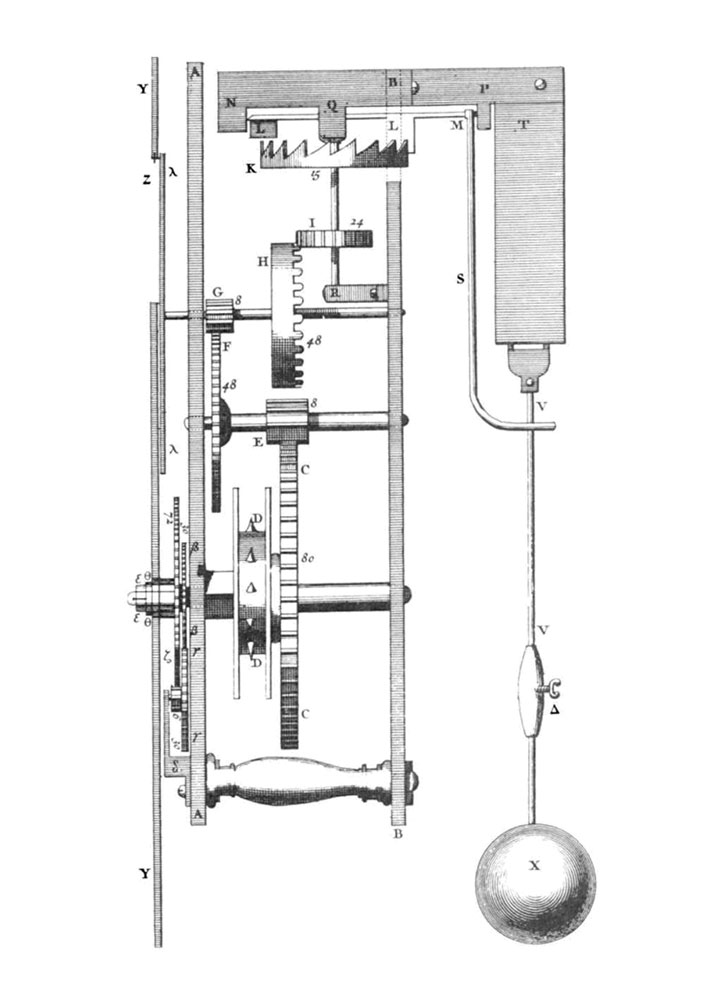

In 1656, Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), the Dutch mathematician, physicist and astronomer produced the first pendulum clock.

Both Gallilei and Huygens were keen to discover a more precise form of timekeeper than the foliot balance clocks in use at the time. With this latter form of clock, a daily error of 15 minutes was not unheard of, making them unsuitable for astronomical observation and other scientific tasks. The advent of the pendulum clock promised a new world of unprecedented precision for 17th century scientists.

The second pendulum clock built around 1673 by Christiaan Huygens, inventor of the pendulum clock (Image: Harold C. Kelly (2007) Clock Repairing as a Hobby: A How-To Guide for Beginners, Skyhorse Publishing, ISBN:160239153X, p.38, fig.13 on Google Books)

However, while the pendulum clock represented a significant step forward in the field of horology, it did have some inherent weaknesses. Firstly, if the amplitude of the pendulum is too great, accuracy is impaired. This was a particular problem with crown wheel escapements. Secondly, the continuous swing of the pendulum creates friction, causing wear that once again impairs precision.

Later, the Englishman Robert Hooke (1635-1703) invented the “recoil anchor escapement” which helped to address such issues. Thereafter, the English clockmaker, William Clement (1638-1704) refined Hooke’s escapement, creating a clock featuring a pendulum that was particularly long (more than one meter in length) and had a small amplitude (2° to 4°). These two characteristics, when applied in combination, delivered a degree of precision measured in seconds, a far cry from the aforementioned foliot balance clocks.

An image of an anchor recoil escapement model used in pendulum clocks based on a design attributed to either William Clement or Robert Hooke in the mid 17th century, originally used as a teaching tool at the Elgin Watchmakers College circa 1935 and now part of the timekeeping collection at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Illinois, May 31, 2013. (Photo by J. B. Spector/Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago/Getty Images)

However, while Clement’s pendulum clock was clearly superior to that of Huygens’, it still possessed inherent weaknesses such as gravity, air resistance and friction at the point where the pendulum pivots.

The reason for my mentioning pendulum clocks is that they share some similarities with the balance (regulating organ) found within a wristwatch. Both the pendulum and the balance within a wristwatch are “oscillators”. Once they receive an impulse from the escapement, they swing back and forth and, in so doing, unlock the escapement allowing the gear train to advance a predetermined amount. It is this metronomic cycle that controls the flow of time.

When a balance oscillates backwards and forwards, the spring at its centre (the hairspring) continuously changes shape, expanding and contracting. Watchmakers often talk about the hairspring “breathing” or “developing”. During this process of expansion and contraction, the balance’s centre of gravity shifts, causing the balance staff to move within its pivots. This creates friction which, in common with said pendulum, causes wear, heightens energy consumption and impairs precision.

Laurent Ferrier Calibre LF619.01: two hairsprings are better than one

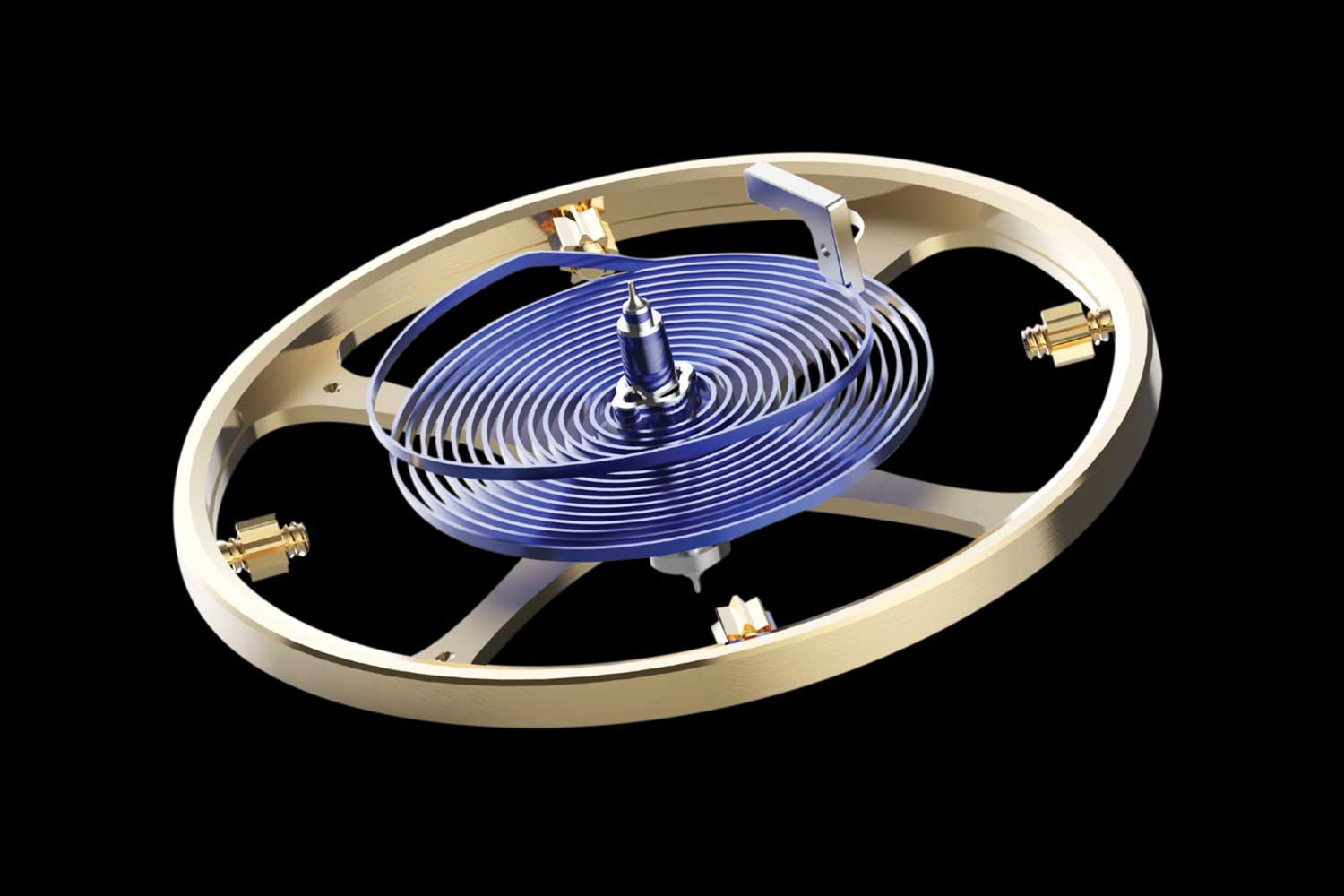

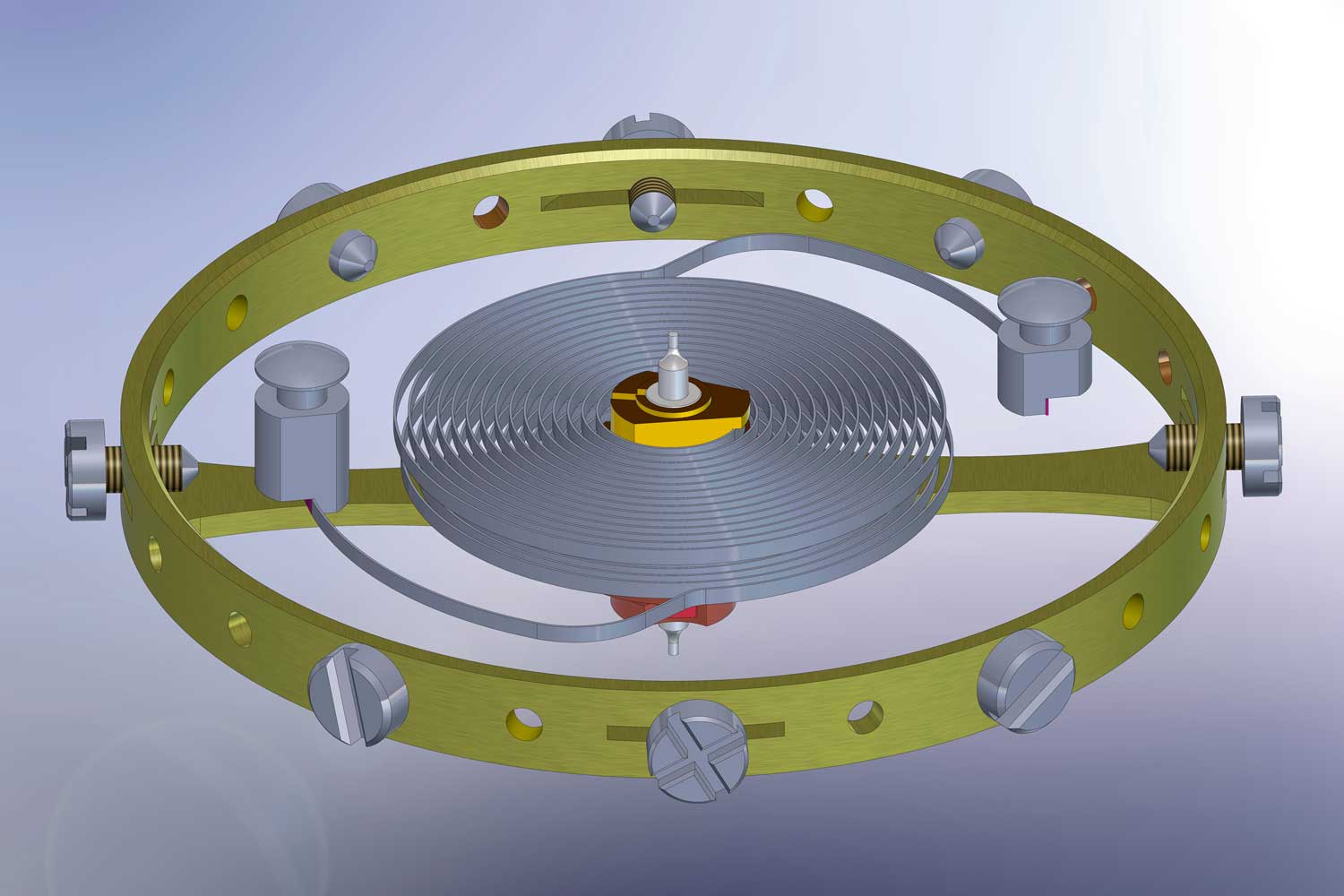

The Laurent Ferrier Calibre LF619.01 is equipped with two hairsprings, spaced 180° apart or “head-to-tail” as the brand prefers to say. As one hairspring expands, its counterpart, positioned opposite, contracts. Close examination reveals that as one hairspring moves to the right, the other moves to the left, cancelling out their individual variations and reducing the friction acting on the balance staff.

So far, so impressive; however, there is another additional benefit of having two hairsprings. When a watch is subjected to a shock, the balance is disturbed. Incorporating two hairsprings means the period that it takes for the balance to return to its optimum frequency is reduced, hence chronometric errors are mitigated.

In addition to the benefits highlighted above, the combination of two hairsprings when coupled with a tourbillon confers superior rate stability. Inevitably, this prompts the question, why don’t all watch companies equip movements with two hairsprings?

Firstly, both hairsprings must mirror one another. Effectively, they should be twins that share the same geometry as small differences will negate the benefits of equipping a balance with two hairsprings. Given this impressive double act requires much time and skill to create, it remains the preserve of low-volume, artisanal watch companies. Secondly, the assembly and regulation are more time-consuming when a balance is fitted with two hairsprings rather than one.

As Laurent Ferrier devotees will already know, the Geneva-based firm is not in the habit of clockwatching, as subscribing to a perfection takes time philosophy.

What is the role of a variable-inertia balance in modern horology?

The Laurent Ferrier Calibre LF619.01 is equipped with a variable-inertia balance. Unlike a “regular” index-regulated balance, the length of each hairspring remains constant. To regulate the movement, inertia weights in the form of traditional timing screws (not to be confused with poising screws), set in the rim of the balance wheel, are rotated. Tightening or loosening the screws makes the watch run faster/slower, similar to altering the length of the pendulum on a vintage clock.

By using a variable-inertia balance, the rate can be set more precisely and will be less prone to positional influence. Furthermore, should the watch be subjected to a shock, it is less likely to require remedial regulation. It’s more time consuming to assemble and regulate a movement fitted with a variable-inertia balance, but then again excellence is seldom achieved in haste.

How does Laurent Ferrier achieve such exceptional hand-finishing?

A notable feature of all Laurent Ferrier watches is that they are always exquisitely finished. When the Classic Tourbillon Double Hairspring was launched in 2010, it signalled to the world that the brand intended to make watches of the highest order.

Close examination of the Calibre LF619.01 reveals a plethora of refined finishes. All signs of machining are carefully removed. The bridges are bevelled by hand with their edges presented at 45° to the vertical plane. Termed “anglage”, this process of bevelling involves using files of various grades to remove burrs. Ultimately, the bevelled edge is refined using a combination of diamond paste and gentian wood to impart a highly polished facet. Some movement parts feature “interior angles” where two bevels meet on an inside corner, a challenging process that can only be performed with great care using time-served hands.

The bridges are adorned with Côtes de Genève motif and, courtesy of their rhodium-plated finish, are destined to retain their factory-fresh appearance for years to come. A closer look at the jewel and screw sinks reveals they are polished to a resplendent gleam. Likewise, close examination of the screws reveals their chamfered slots and rims. Everything is refined to the highest order.

The pièce de resistance is unquestionably the mirror-polishing found on an array of parts, including the click, the tourbillon bridge and the sliding stud holders. These components have been painstakingly polished on a zinc plate in combination with diamond paste and appear black from one perspective and white from another. This form of finishing is widely regarded as the most difficult technique to master.

Having discussed the intricacies of the movement, I now wish to turn my attention to the dial and case. They may appear simple; however, as you would expect of this Swiss company, nothing is ever as simple as it first seems.

The ivory-coloured dial is made using the age-old technique of Grand Feu enamelling. This artisanal approach involves applying alcohol to a dial blank and then dusting it with a powder comprising silica and crushed oxides. This powder-coated dial blank is then placed in an oven and heated to approximately 800° C. Once it has assumed the desired shade, it is removed from the oven, allowed to cool and the process is repeated again and again.

Due to the extremes of heat, air bubbles can appear on the dial surface or it may even crack. This inevitably leads to many dials being discarded. However, those that pass muster will retain their new appearance forever and confer an enduring charm that will never fade.

The dial is fitted with Assegai-shaped white gold hands that collaborate with elongated Roman numerals to express meaning. The small seconds display, positioned at 6 o’clock, is driven directly by the tourbillon cage below and is delineated from the rest of the dial with a fine circular frame.

Everything looks genteel, seemly and softly spoken. For example, the galet-style case replicates the smooth appearance of a pebble honed by nature. There are no sharp case edges, instead arcing contours caress the wrist. This sensitivity to ergonomics extends to the lugs which gently curve downwards, coaxing the strap to encircle the arm. Even the onion-shaped crown with its neat, fluted grip is optimised for ease of manipulation.

The lasting legacy of the Classic Tourbillon Double Hairspring

The appearance of the Laurent Ferrier Classic Tourbillon Double Hairspring represents the epitome of elegant restraint. The model is blessed with a pure face that shuns unnecessary adornment, promising to articulate the prevailing time for many years to come. Moreover, the decision to use Grand Feu enamel and white gold hands means the appearance of the dial will never change; its enduring beauty is guaranteed.

The mechanical vista to the rear is equally impressive. It unites a highly desirable tourbillon mechanism with two hairsprings. In addition, this mechanical tour de force is garnished with several additional refinements along with some of the finest finishing in existence. When the Classic Tourbillon Double Hairspring was launched in 2010, it blindsided the watch industry’s old guard thanks to its ultra-refined execution. Its brilliance was widely recognised, culminating in the model receiving the Men’s Watch Prize at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG).

With time the cognoscenti have become accustomed to the ultra-refined composition and execution of the brand’s watches. However, back in 2010, when the Classic Tourbillon Double Hairspring was unveiled, its technically ambitious specification proved a revelation. It demonstrated an inordinate amount of boldness and courage on the part of the brand’s founders; an approach that makes the word “audacious” seem highly appropriate.

Read more on laurentferrier.ch

Tech Specs: Laurent Ferrier Classic Double Spiral Tourbillon

Reference: LCF001.02.J1.E09

Movement: Manual-winding Calibre LF619.01; 80-hour power reserve

Functions: Hours and minutes; small seconds; tourbillon

Case: 41mm × 12.5mm; yellow gold; water-resistant to 30m

Dial: Grand Feu enamel ivory

Strap: Brown alligator strap with pin buckle or folding clasp

Price: 185,000 CHF (excl. taxes)

Laurent Ferrier