Berneron Introduces The Quantième Annuel

News

Berneron Introduces The Quantième Annuel

When Sylvain Berneron introduced the Mirage two years ago, it landed with a rare mix of being at once conceptually rigorous, mechanically sophisticated and irresistible on the wrist. It went on to take the Audacity Prize at last year’s GPHG, which also saw the debut of the 34mm Mirage with stone dials. Now, Berneron has returned with something altogether new — the Quantième Annuel. The watch is two years in the making and marks his first foray into complicated watchmaking. If you are starting to notice a pattern, you’re not wrong. One new piece every year, always in the first week of September, and he intends to keep that rhythm going for the next decade. That kind of long-range planning says a great deal about the rigour with which he approaches not only design and development, but the business itself.

What set the Mirage apart — hardly in need of repeating, but still worth mentioning — was the level of obsessive concentration that informed every aspect of the watch. The shape alone, strictly derived from the Fibonacci sequence, is hard to get over, and it’s fascinating to see that same intensity of thought and execution now directed toward the notoriously tricky business of a calendar watch.

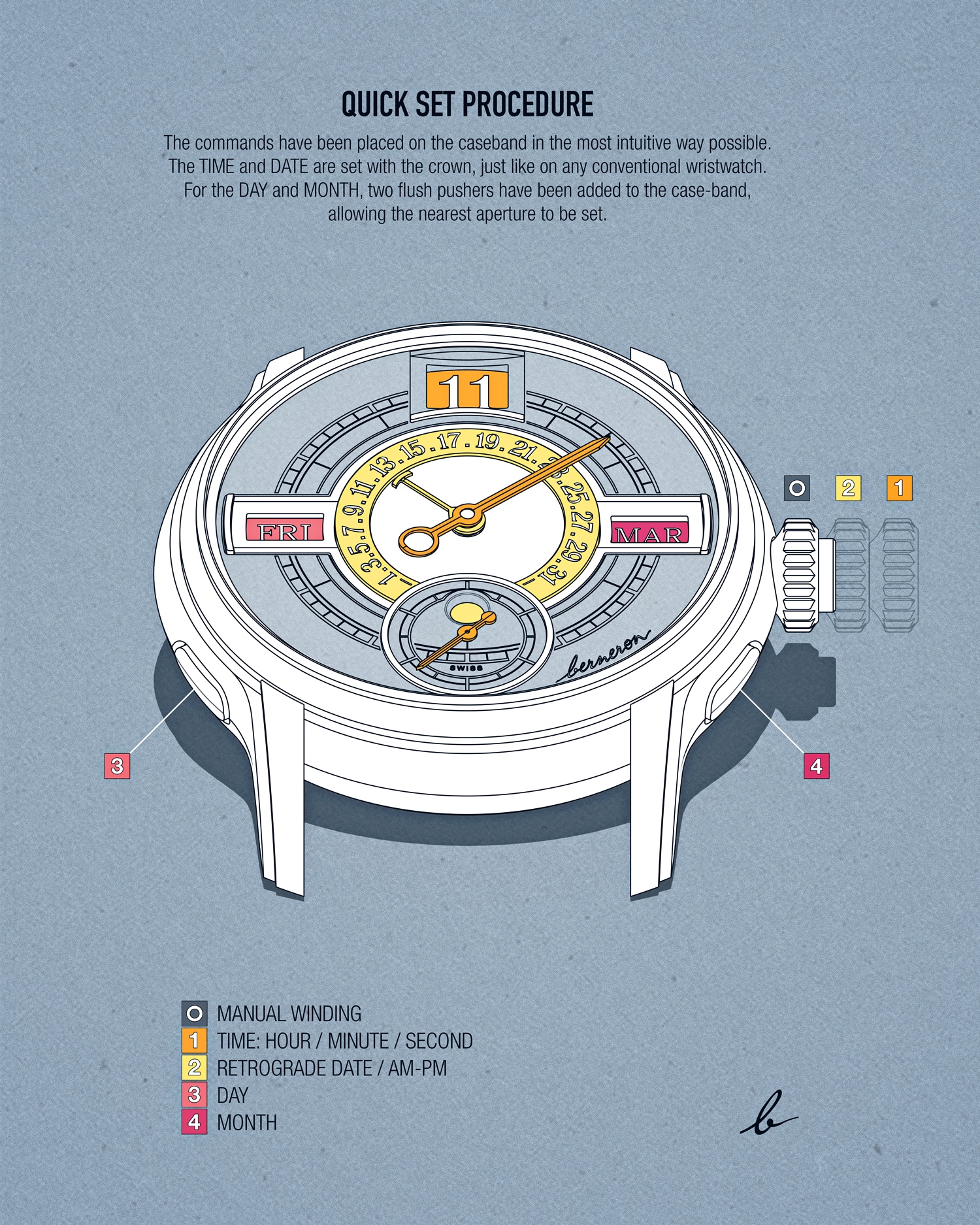

The annual calendar has long lived in the shadow of the perpetual, less sophisticated mechanically (though some, including this one, are just as complex), yet it is just as trying in use. Most rely on recessed pushers around the caseband, each meant to be prodded with a stylus. Each time the watch is picked up again, there’s the business of finding the tool, and then the slow tedium of cycling through days, dates and months depending on how behind it has fallen. It works, but only just; set it the wrong way, or at the wrong time and the result is less a useful complication than an expensive object lesson in what not to do. Besides that, the “dead zone”, the switchover period during which adjustments risk damaging the mechanism can vary from watch to watch depending on the lever design. The convention is 8pm to 3am, though examples with a danger zone stretching from 4pm to 1am are not unknown. The onus, therefore, is on the wearer not only to remember their watch’s dead zone, but also to know whether it is AM or PM. Any one of these inconveniences is often enough reason to leave the calendrical aspect of the watch alone.

The Quantième Annuel was born of the desire to make an inherently finicky complication more approachable, more readable and more intuitive. The industry certainly has a tendency to admire and parade complexity as if it were an end in itself but complexity is only worthwhile if it brings something new to the table and better still, when it proves genuinely useful to the wearer.

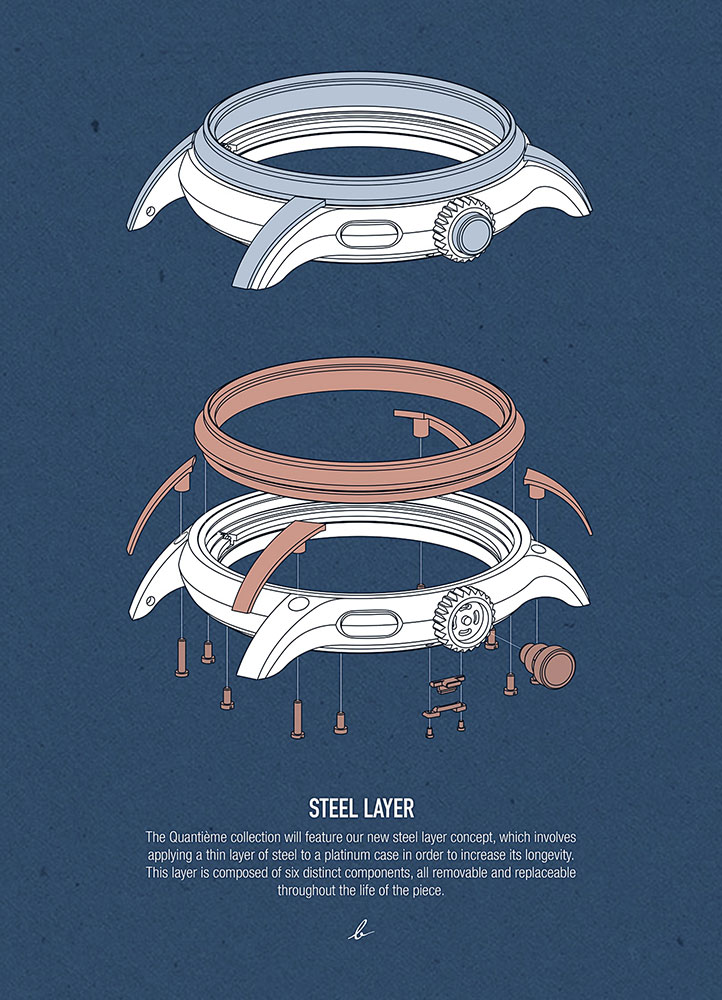

A dial marked by logic and clarity

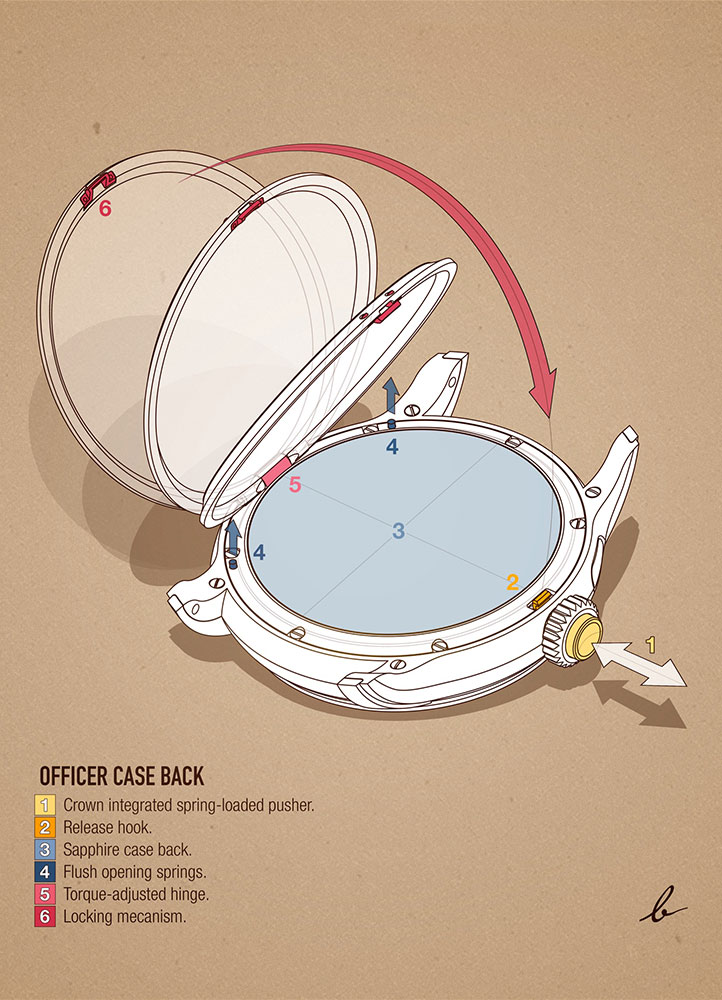

The Quantième Annuel is deliberately classical in its proportions, with a platinum case measuring 38mm in diameter and 10mm in height, complete with a hunter case back. From the beginning, Berneron made it a point to work only with precious metals, and he has held to it here. At the same time, he is pragmatic about the drawbacks of platinum. It scratches easily and is notoriously time-consuming to finish. To address this, the case is reinforced with a modular steel layer, with six key components — the bezel, the four lug steps, and the hunter case pusher — that are replaceable over the life of the watch. Two dial colours are offered — black and silver — and while not limited editions, each will be produced at a rate of just 24 pieces per color per year. True to his philosophy, the dials themselves are crafted in 18K gold, finished with lacquer.

What strikes you first is the remarkable clarity of the dial and the sheer scale of its digital displays. Time is shown in a vertical regulator arrangement with a jumping hour at 12 o’clock, central minutes, and running seconds at six. The calendar, by contrast, is read laterally with the day in an aperture at nine, month at three, and an retrograde date by a centrally mounted hand. A day-night display is neatly integrated into the small seconds. Notably, the hour, day, month, and day-night indicator are all instantaneously jumping indications.

Retrograde perpetual calendars were first pioneered by Patek Philippe in 1937, a lineage that continues today with the ref. 6159. The Quantième Annuel takes the same basic premise, adopting the lateral arrangement of day, date, and month but on a far grander scale. The difference lies in the underlying architecture. In Patek’s version, the day and month are displayed on small discs that sit to the sides of the movement, which forces the apertures outward and compresses the typography. In the Quantième Annuel, the day disc extends almost to the full radius of the movement, while the month disc encircles the central pinion. The result is a layout that allows the apertures at nine and three o’clock to sit wide across the dial with larger, more legible letters, and a dial that reads with a natural balance at a glance.

At the same time, the problem with analog date displays has been addressed. In such displays, the hand moves in constant angular steps since it is driven by regular gears. However, the date numerals vary in width. To compensate for this, the spaces between numbers are made unequal, so the hand always moves the same distance. But this results in a dial that looks uneven, especially around the 20s and 30s. The solution here inverts that logic. Rather than altering the spacing between numerals, the angular pitch of the hand is varied to match the visual width of each numeral, preserving balance and legibility across the scale.

The main event, however, is how easy it is to set the calendar. Time and date are adjusted in the usual way, through the crown, as on any ordinary watch. The day and month are advanced by a pair of pushers in the case band each one directly linked to its nearest aperture. This makes what is usually a fiddly, tool-dependent exercise into something you can do in seconds, with no more ceremony than pressing a button.

Moreover, unlike standard annual calendars where the date has to be advanced forward by three days at the end of February during common years and two days in leap years, the Quantième Annuel only has to be corrected during common years whereas leap years are accounted for. While the patents are still pending and cannot yet be disclosed, what can be gathered is that the program wheel goes beyond the usual encoding of 30- and 31-day months. February itself is built into the system as a 29-day month. Most of all, it does not have a forbidden time window; the calendar can be adjusted anytime without risk of damaging the mechanism.

Additionally, it incorporates a safety mechanism that automatically resets the date to the first day of the next month. For example, if the month corrector is pressed on January 31, the display advances to February 1 rather than the non-existent February 31.

Given the complexity of the annual calendar module (two patents filed, and employs a grand lever) the question was why not a perpetual calendar? Berneron’s answer was characteristically direct: “A QP module adds a lot of volume. It would be like driving around every day with a trailer hitched to your car, just because you’ll use it once every four years.” Hence, he dispensed with the perpetual and drew two clear benefits: the freed volume allowed for an officer case, something to be enjoyed daily, and the dial remained clean and legible, unencumbered by the four-counter layout he considers little more than visual clutter for a function seldom used.

Calibre 595

The Calibre 595 is a hand-wound movement, named for its height of 5.95mm. At first glance, it would seem that a self-winding calendar watch would make more sense since it’s less likely to run down, and when it is off the wrist it can live on a winder, sparing one the nuisance of resetting everything. However, this one has a generous power reserve and is unusually easy to set, and the reward is the movement itself which has a layout and level of detail best seen unobstructed through the sapphire back.

Side profile of Berneron’s hand-wound Calibre 595, showing the twin barrels and symmetrical layout in 18K gold

A casual glance at the caliber makes clear that its arrangement is anything but conventional. The gear train, for one, is nowhere in sight and the winding train dominates the rear view of the movement. Berneron designed it to echo the cross-shaped layout of the dial. Power management was an obvious challenge; at its peak load, the watch must drive four jumps and a retrograde action at midnight on the last day of the month. The energy for each indicator is gradually accumulated and stored locally in a return spring by means of a snail cam, rather than being drawn directly from the mainspring at the moment of the jump, which would otherwise sap amplitude.

Driving all of this is a pair of serially coupled barrels, providing a substantial power reserve of 100 hours. The winding train runs laterally across the movement from right to left, beginning with the crown wheel, then the click wheel positioned at the centre, and finally the barrel ratchet. The first barrel engages the second, located at 12 o’clock, which in turn drives the gear train downward to the balance wheel at six o’clock.

While the Mirage was conceived around asymmetry, the Quantième Annuel is resolutely symmetrical. Yet it carries forward the same vocabulary of finish established in the Mirage. Both the base plate and barrel bridge are made of solid 18k gold with the plate given a frosted surface and the bridge adorned with a guilloché motif that resembles Geneva stripes. These are renderings but in the finished watch, the anglage on the bridges will be executed by hand, while every screw is black-polished and the large barrel jewel will sit in a polished countersink. The free-sprung balance wheel is held beneath a rounded and polished bridge with its holding brackets satin-finished.

In the end, the Quantième Annuel shows that innovation in watchmaking is less about the multiplication of complications nor cleverness for its own sake. Rethinking them purely for the sake of intellectual satisfaction may be exciting enough, but it seldom makes a usefully better watch. What he has done is taken one of the most recalcitrant mechanisms and render it clear, intuitive and mechanically coherent, while holding to the same uncompromising standards of material and finish established with the Mirage. It is a calendar reduced to its essence, stripped of fuss, and made more remarkable by the sheer effort, thought and expense devoted to solving problems most have given up trying to solve.

Tech Specs: Berneron Quantième Annuel

Movement: Manual-winding 18K gold Calibre 595; 3Hz or 21,600 vph; 100-hours power reserve

Functions: Jumping hours; minutes; small seconds; annual calendar with retrograde date and instantaneously jumping day, month and day-night indicator

Case: 38mm × 10mm (45mm lug-to-lug); platinum with steel layer; water-resistant to 30m

Dial: Lacquered 18K gold with 18K white gold hands

Strap: Barenia leather strap

Availability: 24 pieces in each colour a year

Price: Preferential price of CHF 120,000 for 2026, CHF 130,000 for 2027 and CHF 140,000 for 2028 (prices excl. VAT)

Berneron