A Closer Look: A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk Date in Pink Gold

Reviews

A Closer Look: A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk Date in Pink Gold

The A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk was based on an idea originally conceived by Günter Blümlein, who, together with Walter Lange, resurrected the company in the aftermath of the Quartz Crisis. Its digital display took inspiration from a five-minute clock Ferdinand Adolphe Lange helped create for the Dresden Semper Opera House in 1841. When Anthony de Haas joined the company in 2004, he immediately set to work on bringing the idea to life. It would take five more years before the Zeitwerk was finally unveiled in 2009, in the depths of a global recession. It became the first mechanical wristwatch to feature a fully jumping hours and minutes display, and it was peculiar in the sense that it was a dramatic departure from anything Lange had created before or since, and from anything seen in haute horlogerie more broadly. Philosophically, a full jumping digital display has, perhaps, more in common with automatons than traditional complications. They are pre-programed and performative. One mimics life, and the other the behavior of an electronic watch, or time as it is written. Despite arriving 15 years after the brand’s inaugural 1994 collection, which included the Lange 1, and a decade after the Datograph, the Zeitwerk has become every bit as iconic. It remains one of the very few watches that display both hours and minutes on jumping discs.

The Zeitwerk has since also served as a platform for chiming complications including the Decimal Strike and the decimal Minute Repeater, which are some of the most conceptually compelling watches Lange has ever produced. While in most decimal repeaters, adapting to base-10 logic largely involves redesigning cams and driving teeth, the digital display eliminates traditional motion works entirely, forcing a complete rethinking of the striking mechanism. In 2019, Lange introduced a comparatively smaller complication to the Zeitwerk – a date. But the execution was no less elaborate and intriguing. It retained the visual purity of the original digital time display by integrating the date in a ring-shaped format around the periphery of the dial.

At the time of its launch, the Zeitwerk Date introduced significant upgrades over the original Zeitwerk, including stacked, serially coupled twin barrels for an extended power reserve but the standard Zeitwerk has since been updated with the same base movement. Six years after its debut in white gold, the Zeitwerk Date is now being introduced in pink gold.

In contrast to the time-only Zeitwerk, which measures 41.9mm by 12.2mm, the Zeitwerk Date is 44.2mm by 12.3mm. Accommodating a date complication without sacrificing the clean layout of the original means, unavoidably, an increase in size. However, the larger diameter relative to its thickness gives the Zeitwerk Date more refined proportions, making it feel slimmer and more balanced on the wrist.

Though rarely discussed, Lange’s pink gold is a distinctive alloy that is less intense than red or rose gold, but more vibrant than standard pink gold. It differs by using slightly more silver than most 5N rose golds, resulting in a more restrained, elegant pink tone. The lively colour adds a spark to a dial that is otherwise gravely composed, at least until the numerals spring into action.

There are two pushers along the case band – one at 8 o’clock for the date corrector, and one at 4 o’clock for adjusting the hour display, so there’s no need to cycle through the minutes when setting the hour. Notably, the switching action is triggered upon release of the pusher, which eliminates risks of accidental activation. The minutes, on the other hand, are set by the crown.

Like the white gold version, the dial is rendered in slate grey and made of solid silver, while the bridge framing the time display is crafted from German silver that’s been rhodium plated. On the left is a screw that secures the bridge to the plate while on the right is a jewel bearing that supports the arbor of the tens disc beneath. On the periphery of the dial is the date ring, which is a printed glass with transparent numerals. Beneath it is a display ring with a section in red. At midnight, this entire ring advances instantaneously by one step, moving the red section under a new date.

Amid the dial’s restrained palette, the two red accents – the date and the end zone of power reserve indicator – catch the eye instantly. They inject just enough colour to animate the display without undermining the mechanical seriousness of it. Indeed, it’s a quality that’s easy to overlook given how effortlessly and rapidly the indications switch over. All the discs, four in this case with the addition of the date, carry significantly more inertia than traditional hands. As such, a remontoir d’égalité is needed to ensure that power delivery to the escapement remains stable, while the energy required to drive the jumping discs is concentrated during the once-per-minute rewind cycle. Additionally, to handle the torque needed to switch the heavy date ring at midnight, a separate return spring is required in this version of the Zeitwerk.

The Calibre L043.8 within comprises of an astonishing 516 parts, which is significantly more than the Calibre L043.6 in the time-only Zeitwerk with 451 parts and even the L001.1 in the Double Split with 465 parts.

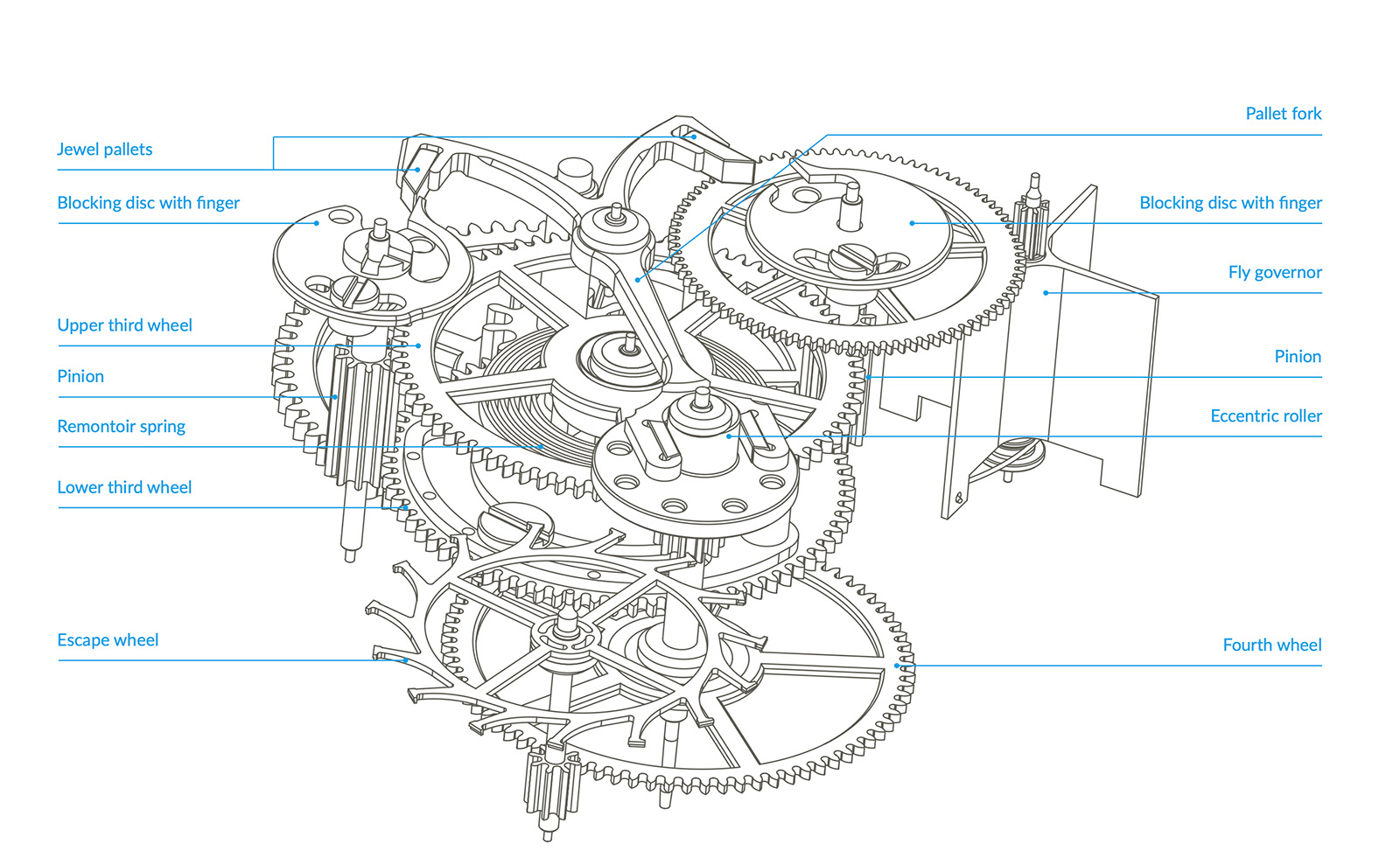

Remontoir d’égalité

Compared to fully jumping digital displays, watches with a jump hour and retrograde minutes are significantly more common. The mechanism used to facilitate the jump is well known. In most cases, the hour jump is powered by the return force of the retrograde action. The energy is accumulated and stored locally in a return spring by means of a snail cam, rather than drawn directly from the mainspring at the moment of jump.

However, the dynamics change dramatically when there are three jumping discs. Unlike a retrograde mechanism that stores energy and releases it once per hour, a digital display like the Zeitwerk’s must physically drive all three discs forward directly from the going train due to its high inertia, and it must move at least one disc every 60 seconds.

This poses two critical challenges. The torque required is both high and sharply timed, and it occurs frequently. To maintain consistent jumping without compromising timekeeping, Lange implements a remontoir d’égalité on the third wheel of the going train. At a glance, it might seem paradoxical. If the remontoir spring powers both the escapement and the jumping display, how can it possibly isolate one from the other? The answer is simply that it is the re-winding of the spring that powers the jump and the unwinding that powers the escapement.

The mainspring barrel delivers energy to the lower third wheel, which is fixed to its axle. Around this axle is the remontoir spring. One end of the spring is attached to the lower third wheel, while the other is fixed to the hub of the upper third wheel, which is rotatably mounted on the same axle. As the axle attempts to rotate, the lower third wheel tries to turn with it, but it is normally blocked by a locking mechanism that consists of a pallet lever engaged with blocking discs that alternate locking the motion. Because the lower third wheel is immobilised, the torque from the barrel winds the remontoir spring instead, building tension between the fixed lower third wheel and the free upper third wheel.

This upper third wheel, now under spring tension, transmits energy to the escapement through the rest of the going train. This transmission is continuous and steady, defined by the stored energy in the spring instead of the fluctuating force from the barrel. Therefore, as long as the lower third wheel remains blocked, the remontoir spring unwinds and drives the escapement with constant torque.

Once per minute, the fourth wheel brings an eccentric cam into position, causing a control lever to pivot. This motion lifts one of the blocking fingers from its pallet, momentarily releasing the lower third wheel. This causes the lever to pivot, disengaging the pallet from one locking tooth while simultaneously engaging the other. In that brief window, the lower third wheel is freed and able to rotate under mainspring torque, re-tensioning the remontoir spring. This sudden motion also drives the display train and jumping digital discs – minute units, tens-of-minutes and hours if needed – before the wheel is locked again.

A fly governor is coupled to this motion, providing resistance and damping to ensure a smooth, controlled jump as well as to prevent recoil or overshoot, especially when not all three discs need to be moved. The key principle is that when the lower third wheel is released once per minute, it receives power from the mainspring and rotates, refreshing the tension of the remontoir spring and simultaneously delivering a powerful impulse to switch the display. The spring is never powering both systems. Instead, it delivers steady energy to the escapement, and once a minute, it is rapidly retensioned and offloads power to the display mechanism. This dual function sequence is what allows the mechanism to separate both timekeeping and display loads.

Full Digital Jumping Display

The hour disc is arranged concentrically around the movement, encircling the smaller units and tens discs. The units and tens discs are arranged concentrically and coaxially, one stacked atop the other, rotating around the same axis. The lower third wheel is the source of motion for the entire jumping display. When it is released once per minute, it turns a pinion that engages the minute units wheel, which is directly connected to the minute units disc. As this wheel rotates, it also meshes with the tens switching wheel, causing it to make one full revolution every ten minutes.

On the underside of the tens switching wheel is a finger tipped with a jewel. After each full revolution of the minute units disc – once every ten minutes – this jewel advances a Maltese cross connected to the tens disc by one step, rotating it exactly one-sixth of a turn. Jumper springs hold the discs in place after each jump to ensure the numerals remain precisely centered in the display windows.

Once the tens disc has completed a full revolution, meaning 60 minutes have passed, it activates the hour display. A pin on the tens arbor pushes a Maltese cross mounted on an intermediate hour wheel, advancing it by a quarter turn. This, in turn, drives the hour ring by by one numeral. A locking system ensures that the hour display can’t shift unless triggered by the tens disc. Because of this layered jumping mechanism, even time-setting required an unconventional solution. Pulling out the crown also blocks the disc mechanism entirely via the control lever in the remontoir. To allow for time-setting (the minutes) despite this, Lange designed a roller-based system. Turning the crown moves a roller across the tips of a contrate hub of the driving wheel. As the roller hops from tooth to tooth, it turns the arbor step by step, precisely and securely advancing the discs in full minute jumps.

At midnight when the hour ring advances from 11 to 12, a date switching finger mounted on the hour gear engages a 12-hour Maltese cross, incrementing it by a quarter turn. At noon, this has no effect. But at midnight, the second quarter-turn causes the date switching cam to engage the date train, a sequence that drives a Maltese cross, a clutch wheel, and a date pinion to collectively rotate the large sapphire date ring by one position.

Because the date ring is large and relatively heavy, it needs its own tension spring to provide supplementary power. This is achieved with a snail cam and a spring-loaded lever. This snail cam is mounted on the units disc. As the units disc advances from 0 to 9, the feeler rides up the increasing radius of the cam and gradually deflects the spring, storing energy. By the ninth minute, the spring is fully tensioned. When the units disc jumps from 9 to 0, the feeler suddenly drops off the sloped edge of the cam, releasing stored energy in a rapid snapback. This burst assists the date switching train precisely when it is needed most, which is at midnight, when the hour mechanism activates the date cam. The mechanism is deliberately geared for instantaneous action, ensuring that the date snaps forward crisply at midnight rather than creep.

Double Barrels & Other Highlights

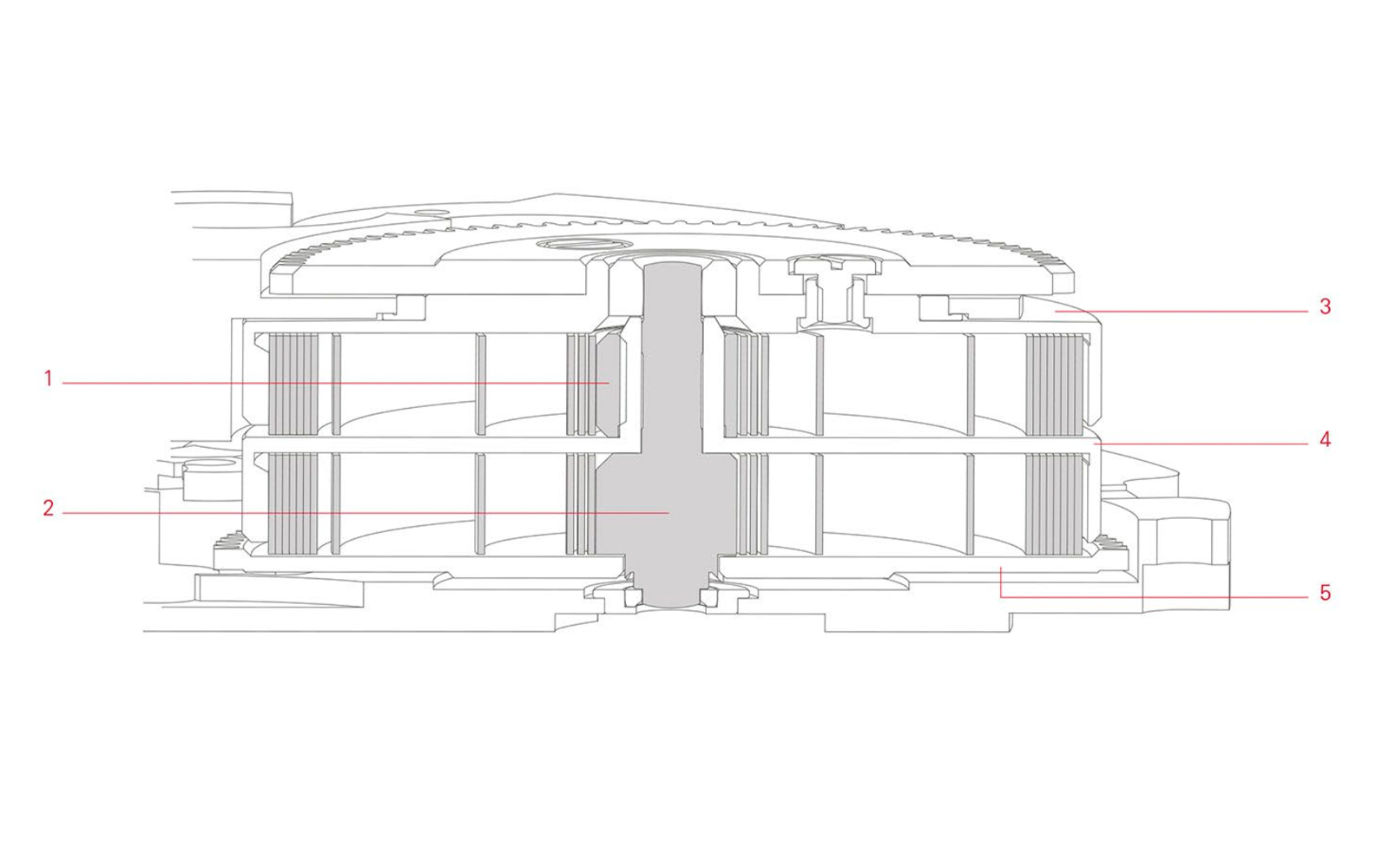

The Calibre L043.8 has a compact, high-capacity twin-barrel construction, designed to provide greater power reserve with only a minimal increase in height compared to a single barrel. The two mainsprings are arranged in series to increase power reserve yet packaged in a compact and structurally stable configuration.

Each mainspring sits in its own barrel (3 & 4), with the upper mainspring coiled around a hollow sleeve (1) that rotates around an extended arbour (2) from the lower barrel. This allows the upper spring to wind the lower one, storing energy sequentially. The entire assembly is supported by a concentric bearing system. The upper sleeve rotates around the arbour, which in turn is supported by a jewel bearing nested inside the central collar of the upper barrel. Axial stability is achieved through stepped shoulders and a radial guide groove that interfaces precisely with the wheel bridge. This architecture keeps the barrels aligned and minimises tilt and friction.

Each mainspring sits in its own barrel (3 & 4), with the upper mainspring coiled around a hollow sleeve (1) that rotates around an extended arbour (2) from the lower barrel. This allows the upper spring to wind the lower one, storing energy sequentially. The entire assembly is supported by a concentric bearing system. The upper sleeve rotates around the arbour, which in turn is supported by a jewel bearing nested inside the central collar of the upper barrel. Axial stability is achieved through stepped shoulders and a radial guide groove that interfaces precisely with the wheel bridge. This architecture keeps the barrels aligned and minimises tilt and friction.

Winding is transmitted through the upper barrel drum, which is fixed to the ratchet wheel, while power is delivered to the gear train via a wheel (5) mounted directly on the lower spring arbour. The result is a compact, efficient system that maximises both stability and energy delivery.

As is characteristic of Lange, all the solutions in the movement are intensely engineered, balancing mechanical finesse with robustness. They are deeply satisfying in their logic and execution, revealing a level of thoughtfulness that rewards close study. Aesthetically, the movement is no less accomplished. Both the balance and escape wheel cocks are hand-engraved with a floral motif. The winding train is exposed in this movement, and it earns the attention; each wheel has individually polished teeth. The centerpiece of the calibre – the remontoir – is visible in all its complexity in the middle of the movement. It is held beneath a linear steel bridge that has been painstakingly finished with 32 internal angles.

Ultimately, the same combination of qualities carries through to the larger question the watch poses: Zeitwerk or Zeitwerk Date? For those drawn to the idea of a fully mechanical digital watch in its most essential form, the original Zeitwerk remains unmatched. But for those who want that same audacity paired with everyday practicality or simply more drama at midnight when all the discs jump, the Zeitwerk Date makes a compelling case. The date has been integrated so thoroughly (and indeed, it’s reflected in the significant premium over the Zeitwerk) that it feels less like an additional function and more like something that was always meant to be.

Tech Specs: A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk Date in Pink Gold

Reference: Ref. 148.033

Movement: Manual-winding Lange manufacture calibre L043.8; 72-hour power reserve; 2.5Hz or 18,000 vph

Functions: Hours and minutes in a jumping numerals display, subsidiary seconds with stop seconds; precisely switching ring-date display, UP/DOWN power-reserve indicator

Case: 44.2mm x 12.3mm; 750 pink gold; water-resistant to 30m

Dial: 925 silver, grey dial with rhodium-plated German silver time display bridge

Strap: Hand-stitched black alligator strap with pink gold prong buckle

Availability: Not limited

Price: Upon request

A. Lange & Söhne