Rolex Files a Patent for a Natural Escapement

Technical

Rolex Files a Patent for a Natural Escapement

The escapement is the beating heart of a mechanical watch, tasked with two fundamental yet opposing duties: regulating the release of stored energy while replenishing the oscillations of the balance wheel. Though straightforward in principle, achieving an escapement that is ideal for a wristwatch, eliminates the need for lubrication at its impulse teeth, and possesses the maturity required for industrial production is one of horology’s greatest challenges. The Swiss lever, despite its known flaws, remains dominant because alternatives have struggled to offer practical advantages at scale.

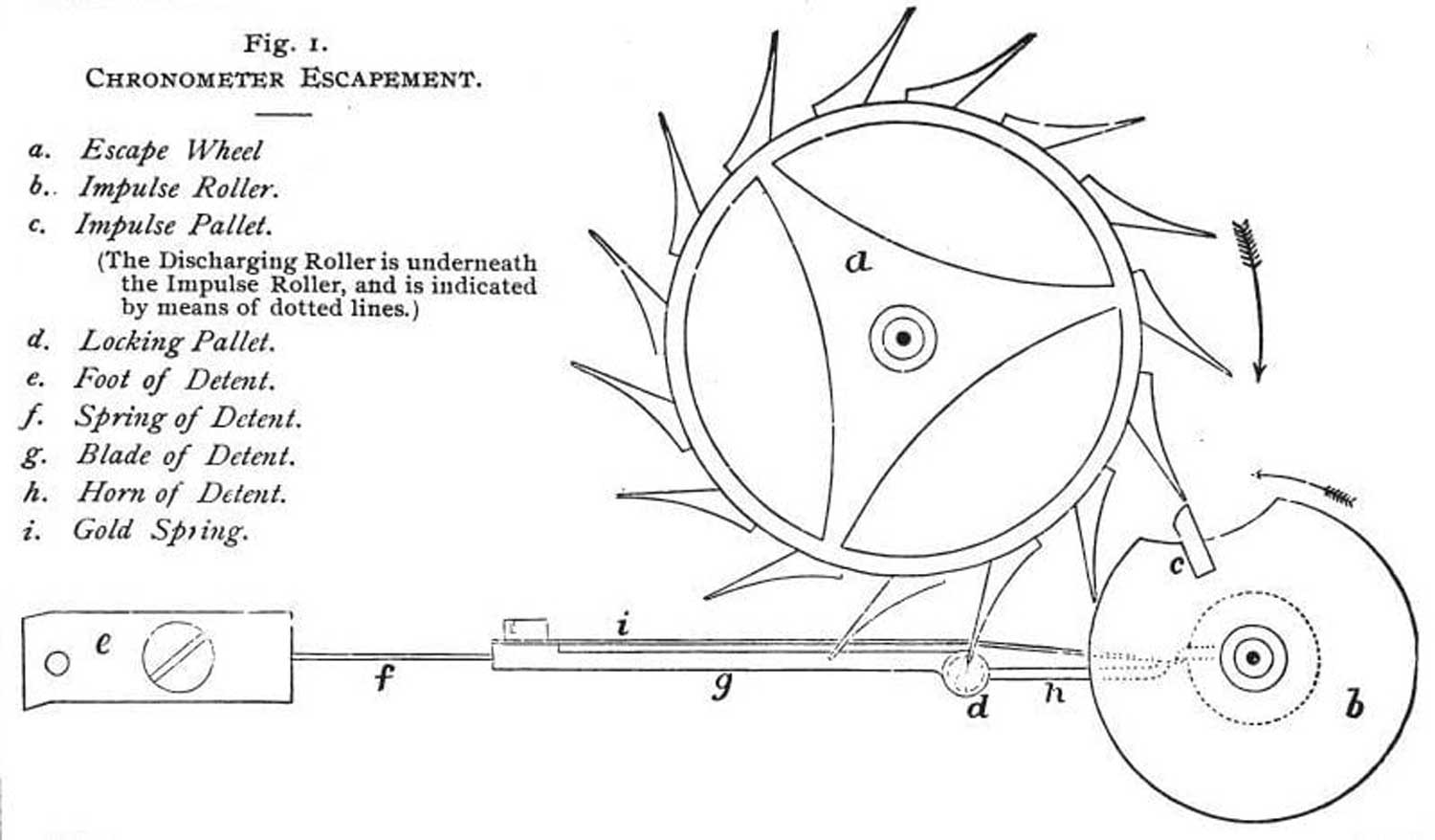

Detent escapements impulse the balance directly but only once per oscillation, creating a lost beat, which is not ideal for a wristwatch. The Co-Axial escapement, developed by George Daniels and industrialised by Omega, was the first major departure from the Swiss lever to achieve true commercial success. It employs a hybrid impulse system that eliminates sliding friction, as both its direct and indirect impulses are delivered tangentially, and at the same time, retains the shock resistance and self-starting behaviour of the Swiss lever.

The Earnshaw chronometer escapement from ‘Britten’s Watch & Clock Makers Handbook, Dictionary, and Guide’ by F.J. Britten

George Daniels’ Co-Axial escapement (Image: Wikipedia). The larger escape wheel delivers impulse directly to the balance, while the smaller wheel transmits impulse to the lever pallet. In this instance, the balance is rotating counterclockwise to unlock a tooth on the larger escape wheel. Thereafter, the smaller escape wheel supplies an impulse to the balance via the lever.

The natural escapement, invented by Abraham-Louis Breguet in the late 18th century, is as captivating as it is vexing, as it offers something none of the others do, which is dual direct impulse at each full oscillation. However, no escapement exists without compromise. The challenge lies in ensuring more benefits than trade-offs, and in the case of the natural escapement, its practical challenges are numerous. The most obvious being its complexity and high inertia. The use of two or four wheels after the going train is mechanically demanding and a higher part count, demands greater precision in assembly and tighter tolerances. Setting aside the finer points, this alone makes it impractical for industrial production.

Breguet invented the échappement naturel, so called because the impulses are delivered directly to the balance wheel, eliminating the need for oil. Shown here is an early configuration of the échappement naturel in the half-quarter repeating pocket watch No. 1135 where the escape wheels are geared together and feature vertical teeth with which they are locked and unlocked by the lever in the middle (Image: Wikipedia)

Yet, Rolex, the most rigorously industrialised brand appears to be revisiting this idea, having recently filed a patent for a tangential impulse double-wheel escapement. It is an intriguing development given the brand’s proven success with the Chronergy, which has yielded some of the most precise movements in the world. Rolex has filed countless patents over the years, including detent and constant force escapements, many of which never materialise in production, but it clearly invests significant time and research into refining fundamental timekeeping technology. Even if this effort remains purely academic, the prospect of an industrially optimised natural escapement is undeniably exciting.

The Classic Natural Escapement

The natural escapement operates with two contra-rotating escape wheels that alternately deliver direct, tangential impulse to the balance in both directions per cycle. In theory, it comes close to perfection, as it effectively eliminates the lost beat of the detent escapement, which made it vulnerable to external shocks during its free swing, while preserving its direct impulse system, thus needing no oil.

As with Breguet’s experiments, the natural escapement primarily exists in two configurations, each with its own set of challenges. The first configuration involves the first escape wheel, driven by the gear train, directly driving the second escape wheel. Each escape wheel features vertical teeth along their bands that serves to lock and unlock the lever in between. The direct coupling means that the second escape wheel relies entirely on the first for motion. However, when the first escape wheel is in a locking or impulse phase, the second escape wheel momentarily loses its driving force; it is effectively floating. Any slight deviation due to play or external disturbances can cause it to shift unpredictably.

Laurent Ferrier’s natural escapement closely follows Breguet’s original design where the first escape wheel drives the second escape wheel directly. Each escape wheel features vertical teeth along their bands that serves to lock and unlock the lever. The escape wheels are fabricated from nickel-phosphorus using LIGA, a microfabrication process that enables the creation of precise, high-tolerance components with complex geometries. Meanwhile, the lever, made of silicon, is a monolithic component with integrated locking surfaces and a guard pin, eliminating the need for pallet jewels.

For a wristwatch, which is constantly subject to movement and shocks, this instability presents a significant challenge. Sudden impacts could cause the free escape wheel to shift slightly out of position, disrupting the locking and impulse sequences. This could result in timing inconsistencies or, in extreme cases, cause the escapement to stall.

The second configuration is such that the twin escape wheels are mounted on mating gears, driven by the gear train. However, the superimposed wheels create thickness and result in high inertia. Both setups require highly optimised engineering to function reliably, making them impractical for the cost and durability constraints of industrial-scale manufacturing. Even if modern techniques like LIGA and high-precision CNC machining allow components to be manufactured with sufficient accuracy, assembly and adjustment remain labour-intensive, making large-scale production seem a pipe dream.

F.P. Journe’s EBHP escapement features a four-wheel configuration, where the twin escape wheels are mechanically linked by intermediate gears. To minimise inertia, the lever is crafted from titanium, while the escape wheels are made of nickel-phosphorous. Instead of a central locking stone, the lever is equipped with two pallets, which alternately lock and release each escape wheel, ensuring greater stability.

Lastly, a classic natural escapement is not inherently self-starting, or at best, it has a very narrow self-starting window. Unlike the Swiss lever, which provides impulse over a broad angular range, the natural escapement delivers impulse asymmetrically and later in the lift angle. This means the balance must travel further before receiving energy. If the balance stops in a position far from the unlocking point, the escapement may not self-start from rest as it lacks sufficient energy from the escape wheel to overcome the locking state, which frequently necessitates external intervention to restart oscillations, making the natural escapement generally not self-starting.

Rolex’s Patent: An Industrial Approach to the Natural Escapement

The Rolex patent aims to overcome certain historical challenges, specifically prioritising robustness, compactness, and manufacturability. It presents two distinct designs: one with a double-layer escape wheel (likely in nickel-phosphorous) and another with a single-layer escape wheel (likely in silicon), favouring simplicity and space efficiency. In both configurations, only the first escape wheel is driven by the gear train, and the other wheel is a follower.

The most obvious difference between the patent and a classic natural escapement is that the lever acts as an intermediary; impulse is no longer delivered directly to the balance axis. This provides greater control over impulse timing while ensuring a stable locking position. Despite this addition, the design retains tangential energy transfer, eliminating the need for lubrication.

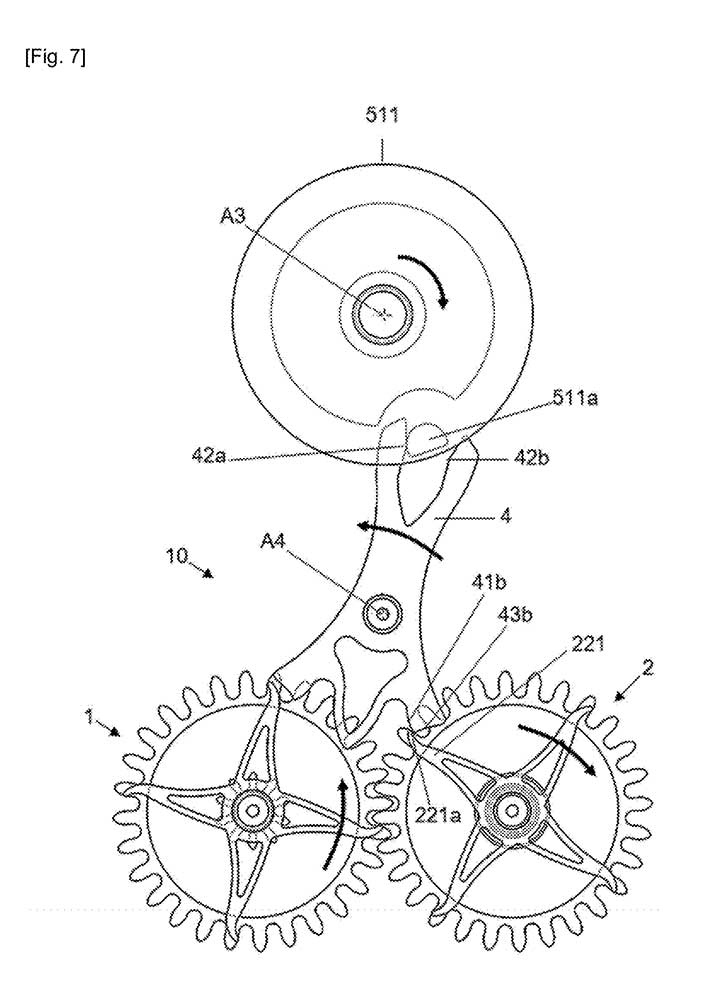

Rest phase. The second escape wheel is locked, the first is free, and the balance is near the end of its oscillation

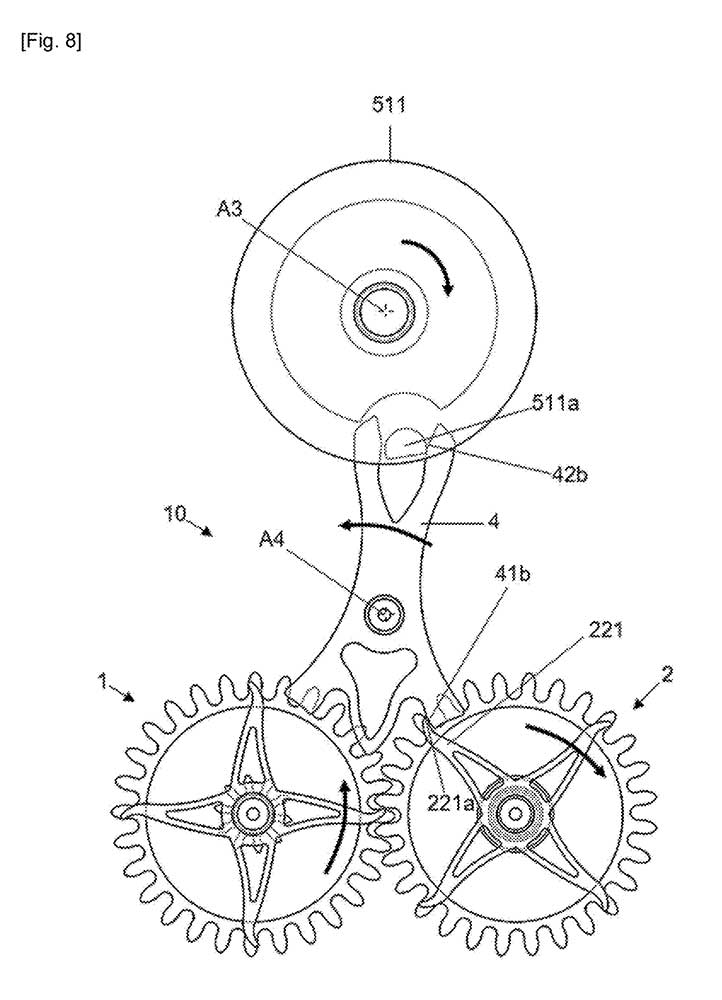

In the first configuration, the design mirrors Breguet’s original concept, in which the locking teeth and drive toothing are on separate planes. Attached to each escape wheel is a four-armed component (121, 221) with elongated, curved profiles terminating in rounded tips (121a, 221a) that engage with the locking surface (43a, 42b) of the lever. These serve as locking teeth, halting the escape wheel in turn.

At rest, the lever alternately locks one of the two escape wheels. For example, a locking tooth (221a) of the second escape wheel (2) engages the locking surface (43b), holding it stationary. At this moment, the first escape wheel (1) is unlocked, having just delivered an impulse in the previous phase.

As the balance wheel (51) oscillates, its impulse pin (511a) interacts with the lever’s impulse surface (42a), pivoting the lever (4) slightly. This pivoting disengages the second escape wheel’s locking tooth (221a) from the locking surface (43b). The tooth (221a) then immediately passes a small rest beak (44b) and directly contacts the adjacent second impulse input surface (41b) of the lever, delivering an impulse. The lever transfers this impulse back to the balance wheel via its second impulse surface (42b), acting on the balance pin (511a).

- Unlocking and start of impulse phase. The balance wheel’s impulse pin (511a) pivots the lever, unlocking the second escape wheel and allowing it to advance.

- Impulse phase. The second escape wheel delivers an impulse via the lever to the balance wheel, sustaining its oscillation.

Following this impulse phase, the second escape wheel (2) continues rotating briefly, simultaneously allowing the first escape wheel (1) to rotate due to their engaged drive toothings (111, 211). Subsequently, a locking tooth (121a) of the first escape wheel engages the lever’s first locking surface (43a), bringing it to rest. When the balance wheel reverses direction for the next half-oscillation, the entire unlocking and impulse sequence repeats symmetrically, beginning with the first escape wheel.

The second configuration diverges from Breguet’s approach by consolidating both the locking and drive toothing within a single plane, a concept reminiscent of Ulysse Nardin’s Dual Direct escapement in the Freak. Here, the escape wheels are entirely planar and monolithic, likely to be manufactured in silicon using DRIE, enabling extreme precision in shaping the teeth while eliminating the need for secondary assembly or adjustments. The lever directly locks and unlocks the asymmetrical locking teeth (121 and 221) on the escape wheels. Without the additional locking component found in the first configuration, this approach prioritises compactness and manufacturability.

While the patent does not explicitly state that the escapement is self-starting, the design characteristics strongly suggest that it is. The combination of impulse occurring before full lever travel and the way the escape wheels interact with the lever ensures that even a small initial motion can start the balance oscillating. The impulse interaction between the escape wheels and the lever occurs at an angle defined by γ (50°–70°), which is smaller than the locking angle α (60°–80°). This means that impulse is delivered before the lever reaches the extremity of its locking position.

Additionally, the locking surface (43a, 43b) of the lever are slightly concave, which enhances locking security while minimising rebound and energy loss upon unlocking. The patent also states that the escapement is designed to work with a balance operating at frequencies of 3 Hz, 4 Hz, or higher, such as 5, 6, 8, or 10 Hz.

The Big Picture

Rolex’s approach to innovation is well-known – methodical and long-term, prioritising incremental yet fundamental improvements, always in service of industrial-scale reliability. The Chronergy escapement was a prime example: a deeply researched, finely optimised evolution of the Swiss lever escapement, designed as a new standard across its entire production.

The Rolex Chronergy featuring broader escape wheel teeth and reduced pallet size improves transmission efficiency by increasing the contact area during impulse phases, reducing drop, and optimizing the locking geometry for more balanced force distribution

The natural escapement, by contrast, has seen little historical development and remains in its infancy. Rolex turning its hand to it carries an implicit aim of producing it at a scale never before seen for a natural escapement. This raises an even more intriguing question: Why pursue an alternative when the Chronergy escapement is already one of the most efficient and robust designs in industrial watchmaking, if not watchmaking?

The answer likely lies in its fundamental advantages. While Chronergy refines the lever escapement with optimised geometry and materials, it does not fundamentally change the way energy is transmitted. It enhances efficiency by improving impulse timing and reducing losses, but its issue is age-old – the need for lubrication on its impulse surfaces.

Whether this patent materialises or remains a purely academic exercise, it shows that Rolex’s pursuit of mechanical efficiency and longevity is a quest that never truly ends.

Rolex