The Detent Escapement In Wristwatches: Dream A (Big) Little Dream

Technical

The Detent Escapement In Wristwatches: Dream A (Big) Little Dream

The winner of the LVMH Watch Prize For Independent Creatives in its inaugural year was a watchmaker named Raúl Pagès, who was awarded the prize for doing something extremely difficult: fitting a chronometer detent escapement to a wristwatch. Pagès was already reasonably well known in the collector community for the Soberly Onyx watch, and like many independent watchmakers who went on to become famous in their own right, he had considerable prior experience in restoring vintage timepieces (F.P. Journe is an obvious example of another watchmaker who followed the same path). Pagès’ RP-1 Régulateur à Détente, however, captured the attention of a much wider audience and the LVMH Watch Prize For Independent Creatives, much to his credit, put him at the head of a large group of nominees which had offered some pretty stiff competition.

Part of the reason that Pagès’ work on the RP-1 is so respected is that in a sense, he set himself an almost impossible task. To understand why, you have to understand what advantages the chronometer, or detent escapement (the two terms are used interchangeably in watchmaking, although obviously not all chronometer watches have detent escapements – in fact almost none do, which hints at the challenges involved in fitting one into a wristwatch) presents in contrast to the virtually ubiquitous lever escapement.

The lever escapement is found in just about every modern watch that doesn’t say Omega on the dial. This escapement is a variation on the older anchor escapement first used in clocks; in watches the consensus is that the first lever escapement was invented by Thomas Mudge, in or around 1756. I often wonder what Mudge would think if he knew his invention would prove indispensable to the development of the modern watch – the number of watches since 1756 which have the lever escapement inside must number in the hundreds of millions.

Animation of a lever escapement, showing motion of the lever (blue), pallets (red), and escape wheel (yellow). (Image: Wikipedia)

What is just as impressive is the fact that with the exception of the co-axial escapement, not a single other watch escapement since then has been effectively mass-produced. The verge, the predecessor in both watches and clocks to the anchor and lever escapements, hung on in some workshops until almost the end of the 19th century (out of, I suspect, professional inertia as much as anything else) and although you can get exceptional performance out of a verge escapement if you really work at it, the odds are against you. There have been probably hundreds of attempts to develop other escapements since the lever first began to tick, but the Robin, chaffcutter, cylinder, duplex, and others too numerous to count have all fallen into disuse.

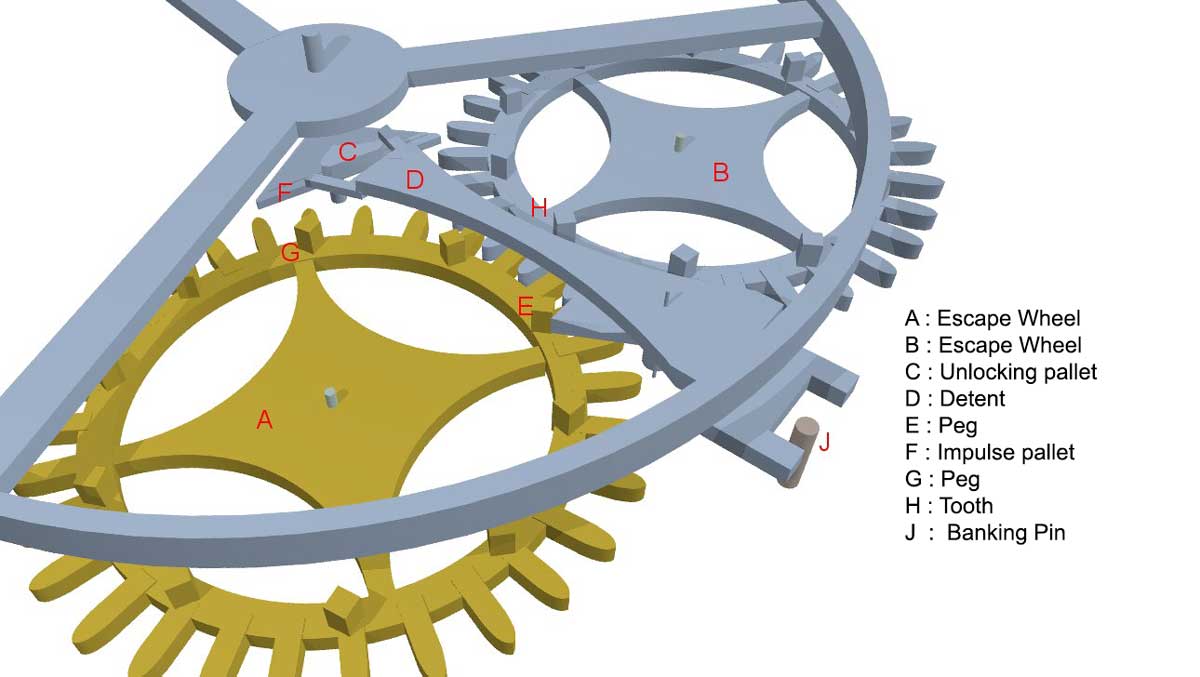

George Daniels' Co-Axial escapement (Image: Wikipedia). The larger escape wheel delivers impulse directly to the balance, while the smaller wheel transmits impulse to the lever pallet. In this instance, the balance is rotating counterclockwise to unlock a tooth on the larger escape wheel. Thereafter, the smaller escape wheel supplies an impulse to the balance via the lever.

Years ago I was scolded by the late Clare Vincent, curator of the watch and clock collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for – as she felt – unfairly disparaging the verge; she pointed out that in her view Jost Bürgi’s cross-beat verge escapement, from 1584, deserved praise and of course, John Harrison famously used a version of the verge escapement in his H4 marine chronometer, albeit it was something of a verge on steroids, with beautifully shaped diamond pallets and the first known spring remontoir in a watch. These exceptions are however, exceptions that prove the general rule that the lever greatly exceeds the verge in practicality; Harrison’s, for instance, proved to be so technically difficult to construct that his escapement never became more widely used – it was essentially a dead end, although a magnificent one – and the first really successful escapement for marine chronometers was in fact, the detent, or chronometer escapement.

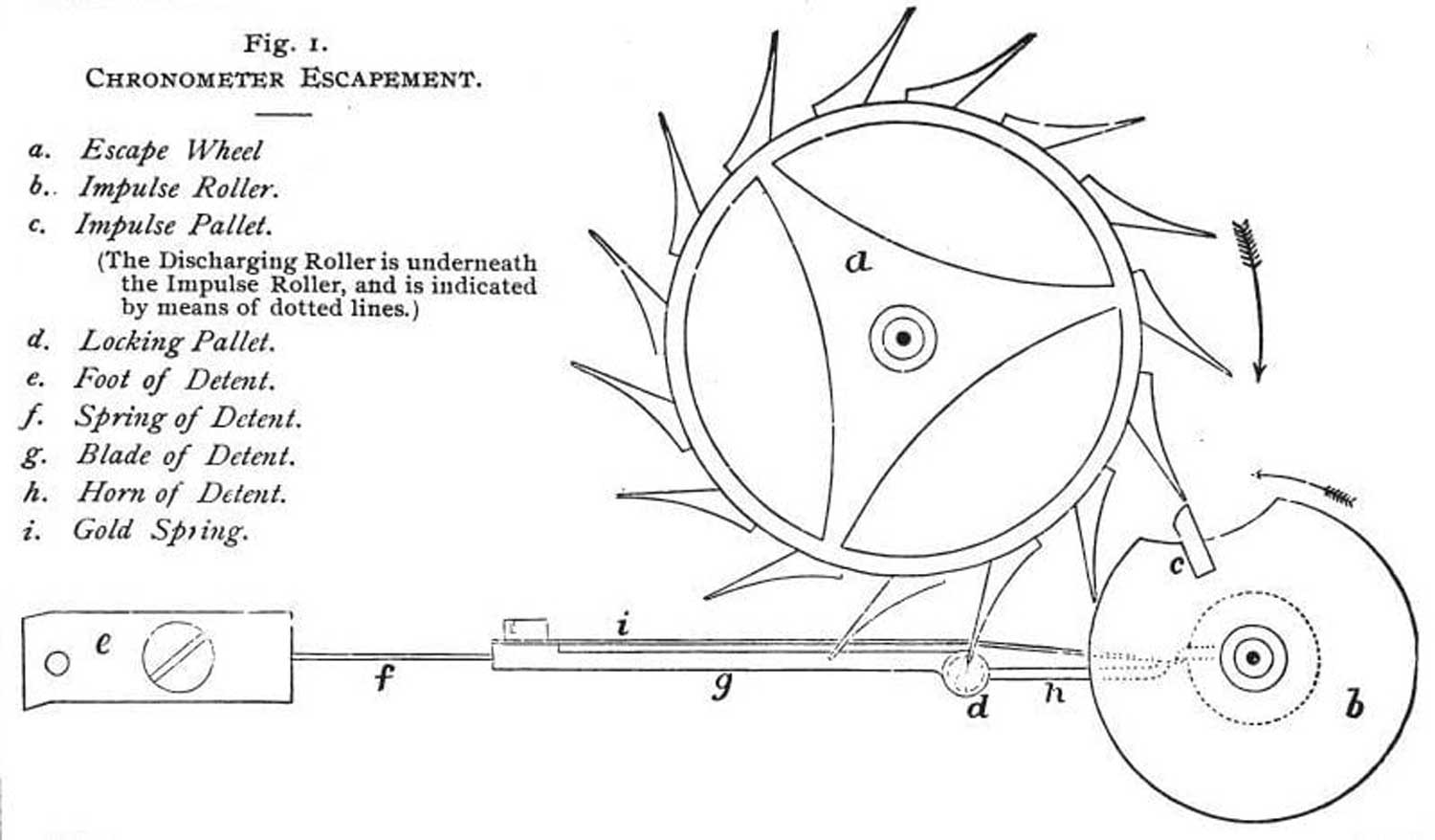

The chronometer escapement has a lot of advantages. Essentially it works by using the escape wheel to directly impulse the balance. The escape wheel is held in place by a long, thin, light lever which is in turn held in place against an escape wheel tooth by a spring – either a blade spring at its foot or by a spiral spring resembling a balance spring. This detent is set up so that it unlocks the escape wheel as an unlocking stone on the balance flicks it briefly aside, and as the escape wheel advances, one of its teeth picks up the impulse jewel on the balance roller, giving energy – impulsing – the balance. The advantages of the escapement are that it is a direct impulse escapement, so it’s inherently more efficient than the lever as no energy is lost in the escapement itself – the lever escapement uses the escape wheel to flick the lever back and forth as the balance rotates and so energy is necessarily lost between the escape wheel and the balance itself. The other advantage to the detent escapement is that, since there’s no sliding friction, it requires no oil; the lever escapement has oil on the lever’s pallet jewels and as the oil deteriorates over time, the amount of friction at the impulse surfaces increases and timekeeping becomes more erratic.

The detent, however, has three big disadvantages. The first is that it only gives impulse in one direction of the rotation of the balance, which in a watch on the wrist can lead to inconsistencies in balance amplitude (a non-issue for the most part in a marine chronometer). The second is that it is not self-starting. A lever escapement’s geometry means that as you wind torque into the going train, at some point the lever will be moved by the escape wheel from its neutral position and the balance will begin oscillating.

The biggest problem with putting a detent escapement in a wristwatch, however, is that the force holding the locking jewel of the detent in place against the escape wheel is very small, and there is no “safety” as watchmakers call it – that is, the geometry of the escapement does not prevent it from accidentally unlocking if the watch gets a shock. The lever escapement, on the other hand, uses “draw” as it’s called – the geometry of the lever pallets against the escape wheel teeth, forces the lever against so-called banking surfaces on either side of the shaft of the lever, making it very difficult to dislodge accidentally. (Most watches historically have used adjustable pins – banking pins – although in some cases the bankings are part of the movement plate itself, which requires a great deal of care in manufacturing as it is difficult if not impossible to adjust the bankings afterwards. The Geneva Seal requires any candidate watches to use solid bankings rather than banking pins).

The idea of using some sort of direct impulse escapement in a watch is, however, very seductive to watchmakers and over the centuries, there have been a number of attempts to adapt it to the wristwatch or to develop some sort of direct impulse escapement suitable for use in a wristwatch. The most famous example is the co-axial escapement, which uses a complex lever for locking the escape wheel and providing draw; the co-axial gives direct impulse in one direction and indirect in the other. It’s not a perfect solution to combining the advantages of the lever and the detent escapement, but it’s very close, and at least theoretically, requires no oil on the impulse surfaces (Roger Smith has told me in the past that he uses a very small amount of oil on the escape wheel teeth, not because the escapement requires it, but rather to reduce the risk of impulse corrosion). The co-axial compared to the lever is more complicated but its use by Roger Smith as well as Omega (which use different versions of the escapement but which operate according to the same principles) has proven its value and practicality, and with it, Omega gets Master Chronometer precision (0/+5 seconds per day maximum variation in rate) and produces hundreds of thousands of co-axial escapements a year.

Other attempts to adapt a direct impulse escapement to the wristwatch, include Breguet’s so-called “natural” escapement. This is a double escape wheel design, in which two counter-rotating escape wheels give impulse to the balance in both directions. “Natural” here refers to natural lift – another term for direct impulse from the balance wheel or wheels to the balance. Breguet was unable to get his design to work satisfactorily but some modern watchmakers have used variations on the design, including Bernhard Lederer, Kari Voutilainen, Laurent Ferrier, and George Daniels himself, who used two separate gear trains for each of the two escape wheels – normally, in a natural escapement, one of the escape wheels is driven by the other, which produces uneven impulse energy.

There have also been attempts to develop single direct impulse designs which don’t rely on the delicate detent – the best known is probably the so-called AP Escapement, which was used in the Jules Audemars Chronometer. This escapement used a lever for locking and unlocking and an escape wheel similar in geometry to a standard detent escapement escape wheel. The risk of accidental unlocking was reduced partly through the geometry of the pallet locking stones (the lever had conventional banking pins, like the lever escapement) but mostly through the use of a safety dart on the lever – a projection which sat very close to the balance roller; the idea was that if the watch got a shock, and the lever started to unlock accidentally, the safety dart would strike the roller, preventing the lever from unlocking completely. It was an interesting design but AP decided not to produce it more widely – it turned out to be very sensitive to frequency; AP had to run it at 43,200 vph, and it was also not self-starting. One of my many memories of Giulio Papi was back in my first tour of duty as a Revolution writer; I asked him if the escapement was self-starting and he chuckled and mimed someone rotating a watch back and forth to get it running. While an escapement not being self-starting is a theoretical disadvantage, I don’t know how much of a real problem it is in real life – the question would only come up if you let your ChronAP, as we called it, run down and then wound it without noticing whether or not it had started up.

This brings us finally, by a long and winding road, to the question of a chronometer detent escapement in a wristwatch – generally speaking, it is a terrible idea; the detent escapement as mentioned above is delicate, gives impulse in only one direction, unlocks accidentally if you look at it cross eyed, and moreover is more difficult to construct than a lever – an escapement whose idiosyncrasies are well know, whose geometry is well know, and from which Rolex gets ±2 seconds maximum deviation in rate per day (albeit with the Chronergy escapement, optimized to obviate some of the uneven impulse energy issues you have with the standard lever escapement). However, if you could adapt the detent escapement for a wristwatch, you would at least theoretically have a more efficient escapement than the lever, which would also have better long-term rate stability as there would be no oil on the impulse surfaces.

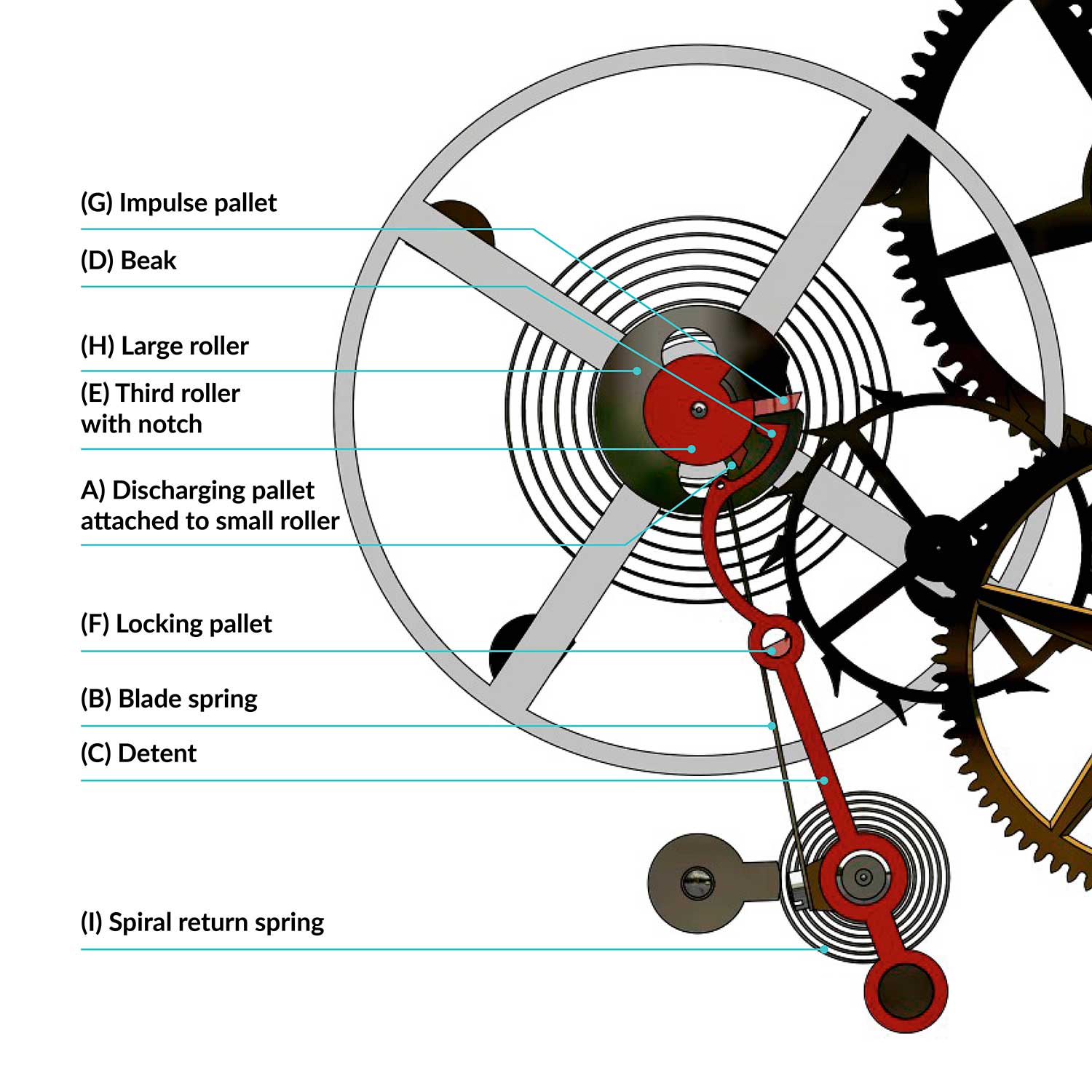

Raúl Pagès particular solution is based on a patent originally granted to Emile James in 1891. James’ design used a pivoted spring detent, with a curved safety beak at its tip, very close to the balance roller. The detent is blocked from moving by the safety beak, which will strike against the roller if the detent gets a shock and it begins to unlock; there is a notch in the impulse roller into which the tip of the beak drops when it is unlocked at the correct time. Urban Jürgensen’s detent escapement works according to a similar principle, although the specifics of the two designs differ in the designs of the detents and safety rollers.

The use of safety mechanisms in detent escapements for the wristwatch may seem a little kludgy at first but safety darts are also found in lever escapements, where the dart prevents the lever from unlocking the escape wheel if the watch gets a shock, in a similar way. In the lever escapement accidental unlocking is however much less likely thanks to the draw from the escape wheel, which holds the lever against its bankings. In wristwatches with detent escapements, the safety system – the beak on the end of the detent, in the RP-1 – is the primary protection against accidental unlocking, and what would be ideal is if a detent escapement could be constructed which provides safety in some way inherent to the escapement geometry, and which was as relatively easy to construct, and relatively simple, as the lever escapement.

During the descending supplementary arc of the balance, the discharging pallet (A) on the small roller, comes into contact with a fine blade spring (B) and displaces the detent (C). The beak (D) penetrates the notch on the third roller (E) and the locking pallet (F) on the detent unlocks the escape wheel, allowing it to advance one tooth forward. Another tooth on the escape wheel falls onto the impulse pallet (G), which is part of the large roller (H), and transmits energy to the balance to make its ascending supplementary arc. Now the beak has been released from the notch and remains in proximity to the periphery of the third roller. The safety mechanism here refers to the beak briefly pressing against the periphery of the third roller in the event of a shock, stopping the detent, which is returned to its resting position by a spiral spring (I) whenever it is displaced.

I think it would be unfair to call the systems used by Pagès and Jurgensen mere workarounds, though. They represent compromises with the inherent disadvantages of the detent escapement but so in a sense does the co-axial escapement, which provides impulse in two directions, and draw, but which is also more complex than the lever escapement and which only gives direct impulse in one direction. Designing an escapement for a stationary clock or gimbal-mounted marine chronometer is in some ways a simpler problem than for a wristwatch since you don’t have to worry about protecting against the almost constant jarring a wristwatch gets; the most extreme examples of how much precision you can get if you don’t have to worry about motion and physical shocks, are high precision pendulum clocks, some of which could keep time to within a second a year or better, but which had to be kept in special enclosures shielded from even minor vibrations (like passing road traffic) and which had pendulums that were electromagnetically impulsed, which also swung in a vacuum.

Every escapement, like any mechanical solution to a practical problem, represents a compromise between the ideal and the real and throughout the history of watchmaking, the difference between the two has grown smaller and smaller, but will never be entirely erased. Enthusiasts love to argue the minute differences in precision required by various chronometric standards, like the COSC chronometer standard, or the Master Chronometer certification, or Rolex’s Superlative Chronometer standard but in practice, such differences turn out to be almost unnoticeable and in a modern, precision-manufactured industrial watch, we are still getting in many cases performance that represents what horologists in the past would have expected only from precision pendulum clocks or boxed chronometers.

This, however, doesn’t mean that experiments like those from Pagès or Urban Jurgensen, with the detent escapement, or those from watchmakers adapting the natural escapement to the wristwatch, are without interest; such work gives modern watchmaking badly needed variety and evidence of the continued ingenuity being applied to some of watchmaking’s oldest problems. The barriers to wider adoption of detent escapements in wristwatches are at this point, perhaps less practical and more to do with the already excellent performance provided by the modern lever escapement, whose behavior is well known and whose design has been refined for over 250 years. If I were an independent watchmaker, I would find experimenting with escapement design irresistible and although I don’t think there is any reason to expect anything to dethrone the lever escapement in terms of practicality and ubiquity any time soon, and such experiments are of inestimable value in preventing watchmaking from stagnating creatively.