The Making of a Masterpiece: Breguet Sympathique No. 1

Auctions

The Making of a Masterpiece: Breguet Sympathique No. 1

The Sympathique clock occupies a singular place among Abraham-Louis Breguet’s inventions. It is a triumph of mechanical imagination that pushed beyond the already extraordinary achievements for which he is known. Unlike the tourbillon, which was designed to average out positional errors or the pare-chute that protected delicate pivots from shocks, the Sympathique was not a refinement of a mechanism but a reinvention of its ecosystem. It introduced the idea that a pocket watch could be wound and set, and in some iterations, even regulated automatically by a master clock into which it docked.

- Sympathique No. 128, sold in 1836 to the Duc d’Orléans

- Breguet Sympathique No. 666 sold in 1814 to the Prince Regent, who became King George IV of Great Britain

That such a concept could be executed at all purely by mechanical means, let alone in the 18th century is astonishing. As George Daniels observed in his book, The Art of Breguet, “There is more mystique surrounding the Sympathique than any of Breguet’s products. Relatively few people have seen one and only perhaps half a dozen know exactly what they do and how they work.”

A pragmatist who valued fundamental advancement over spectacle, Daniels went on to add, “They were never intended to advance the science of horology and made no contribution towards solving mechanical problems and, as a consequence, no increase in Breguet’s fortunes. It is usual with great names to describe one of their works as a crowning achievement. Breguet’s wide diversity of inventions and products makes such an accolade unnecessary. Nevertheless the Sympathiques may stand as a monument to his extraordinary ability to commercialise his talent for producing works of the greatest visual and technical beauty.”

Later, on the following page, he wrote, again with amusing ambivalence: “The Sympathique is an ingenious and amusing toy such as only Breguet could conceive. Certainly no one but Breguet could have produced them, for they need not be considerable. The burden would have taxed a workman to make them and the financial justification could not have been considerable. They can hardly be described as useful or necessary, but great artists are not always motivated by such considerations… The Sympathique is a jewel of misplaced ingenuity in a forest of solid horological endeavours, and their very existence is sufficient reason for their manufacture, for they never cease to amaze and mystify.”

Breguet conceived the clock in 1795. Writing to his son in a letter dated June 26th, 1795, he described his breakthrough with guarded enthusiasm, “I have great pleasure my friend, in telling you that I have made a very important invention, but about which you must be very discreet, even about the idea.

I have invented a means of setting a watch to time, and regulating it, without anyone having to do it. The most coarsely made watch, provided it doesn’t stop, will serve its owner as though he had a garde temps. This is how it works: you have to have a second clock or a marine arranged to receive the watch. The cost of this addition is a day’s work for a workman and the same for the watch.

Then, every night on going to bed, you put the watch into the clock. In the morning, or one hour later, it will be exactly to time with the clock. It is not even necessary to open the watch. There will be nothing visible externally to show where it has been touched. I expect from this the greatest promotion of our future fortune.”

The Sympathique, in both conception and execution, is a testament to both Breguet’s inventive genius and his extraordinary versatility. In spirit, it has more in common with automata than traditional horology, creating a mechanical dialogue between clock and watch that performs winding, setting, and even regulation without human intervention.

The Original Breguet Sympathique Clocks

Just over a dozen Sympathique clocks were produced by Breguet and his successors, including one by his brightest pupil, Louis Rabi. They can be divided into two categories by function: one that sets the time and regulates the rate of the watch, and the other sets the time and winds the watch. Daniels in The Art of Breguet went on to describe three different mechanical executions that fall within the two main categories. They differ primarily in how the time is set on the pocket watch, specifically in what triggers the setting, where the mechanical logic resides, and how the motion is transmitted.

In the first type, as in the Demidoff Sympathique No. 430, sold to Prince Anatole Demidoff in 1830, which both sets the time and regulates the rate, the initiative comes from within the watch itself. The role of the clock is simply to release the setting mechanism inside the watch at a fixed time, at 12:00. Once released, the barrel inside the watch drives the train that moves the setting wheels. These wheels carry steel blocks that either pass harmlessly over the setting lever if the watch is already at the correct minute, or if it is slightly fast or slow, the appropriate block nudges the lever to align the minute hand to 12:00. This same interaction triggers a regulation action by shifting the position of the index on the balance spring via a set of pawls engaging a regulating rack, correcting the rate by up to ±3 minutes per release. Crucially, all intelligence including the detection of error, decision to act, and execution, resides in the watch. The clock merely releases the mechanism.

- The diagram, taken from The Art of Breguet by George Daniels, showing the setting and regulating system of the Sympathique No. 430

- An enlarged view of the regulating mechanism with two pivoted pawls mounted on the minute hand arbour. If the watch is fast or slow, one of the pawls engages a toothed rack that shifts the regulator accordingly. Image: The Art of Breguet by George Daniels

In the second type seen in the quarter striking Sympathique clock No. 5 made by Louis Rabi, the clock winds and sets the watch every half hour. Here, it is the clock that actively performs the work, both in winding the mainspring and setting the time. The striking train drives a cam and levers that push a pin upward into the watch, which then mechanically sets the watch to the half hour. Meanwhile, a remontoir mechanism in the going train of the clock delivers energy by pumping a lever three times per half hour, incrementally winding the watch through a ratchet and pawl system. Unlike the first type, this watch has minimal internal logic. The setting is entirely based on external motion, and the watch does not regulate its own rate. It receives time correction and winding input from the clock.

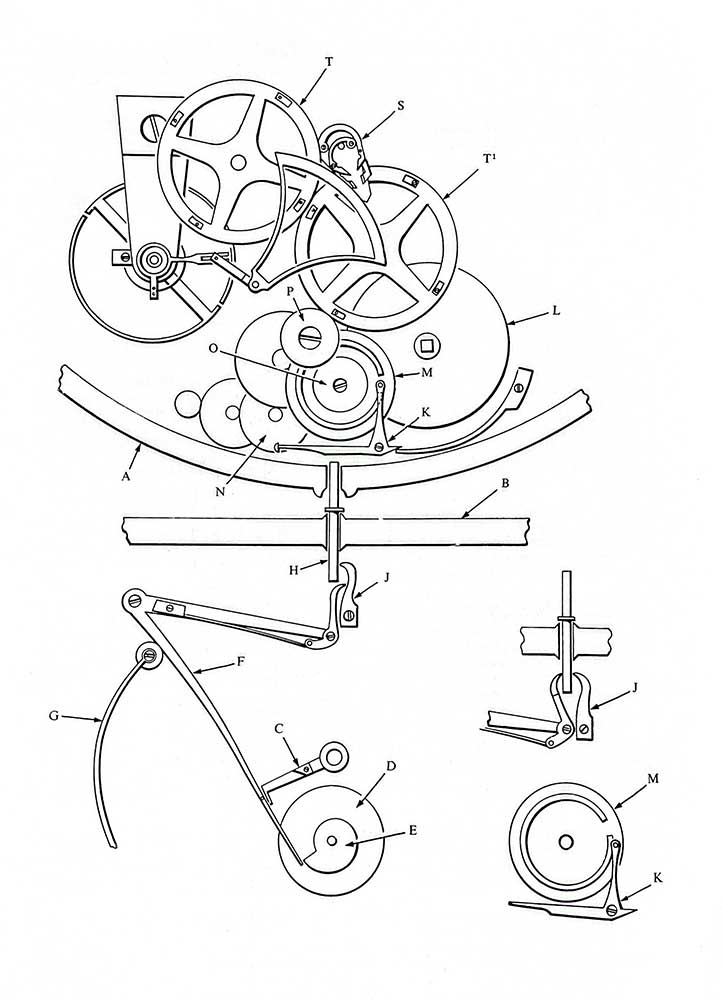

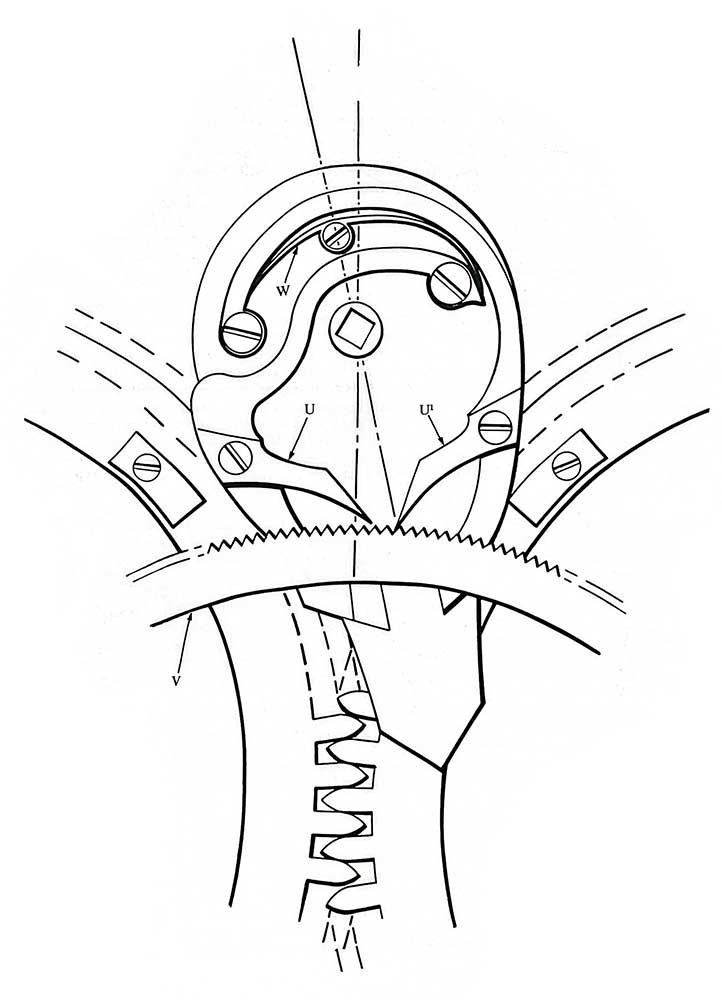

Image from The Art of Breguet shows the Sympathique mechanism by Louis Rabi, specifically from clock No. 5. The strike train powers the time-setting mechanism, in which a cam on wheel (A) drives a lever (B) that pushes a pin (C) into the watch to reset the minute hand to the half hour. The going train, via a remontoir, powers the winding mechanism, which pumps a lever (T) three times per cycle; this raises a pin (U) that actuates a ratchet (V) inside the watch to wind the mainspring via the ratchet wheel (W).

The third type, as exemplified by the quarter striking Sympathique No. 128 made for the Duc d’Orléans, is the most complex and sophisticated of all known systems. In this design, the clock automatically winds and sets the watch once every 24 hours, precisely at 3:00 AM. The entire winding and setting system is powered by the strike train in the clock. A dedicated winding shaft in the clock aligns with a square in the watch’s movement; if the squares are misaligned when the watch is placed in its cradle, a spring compresses and then pushes the shaft into engagement once alignment occurs during rotation.

This is the release and control system for the automatic winding operation in the Sympathique No. 128. Every 24 hours, a cam on the 24-hour wheel (D) lifts the setting lever (C), which hooks detent A to prepare for release. At exactly 3:00 AM, the cannon pinion (F) triggers the final drop of the mechanism, unlocking the fly (B) and engaging the winding shaft (J). (Images: The Art of Breguet)

Watch-side mechanism of Sympathique No. 128. The clock’s winding shaft powers a lifting piece (B) that raises levers (S) to reset the hands to 3:00, while winding the mainspring. Once fully wound, internal stopwork trips a lever (C) to halt the winding train. (Images: The Art of Breguet)

Within the clock, a cam on the 24-hour wheel triggers a sequence of levers that releases the winding train and engages the setting system. The winding shaft enters the watch and begins to rotate, powering not only the mainspring but also the hand-setting operation. Inside the watch, a three-armed rotating lifting piece raises two articulated setting levers that engage the motion works, setting both the minute and hour hands to 3:00. This is a hard reset rather than a correction; the hands are driven to the fixed time, regardless of their previous position.

Winding stops automatically once the watch is fully wound. A stopwork linked to the barrel arbour advances with each turn, and after four rotations, it triggers a linkage that sends a mechanical signal back to the clock to disengage the winding train. The same linkage also actuates a state-of-wind indicator inside the watch. Importantly, safeguards are built in. If the watch is not present in the cradle, a pin in the clock detects its absence and locks the flywheel, preventing the release of the winding train. Without this safeguard, the train would continue running until the clock’s striking power was depleted.

Compared to other types, this third system achieves a greater degree of autonomy and integration. While the first type performed correction by nudging the minute hand based on detected error, the No. 128 executes a full mechanical override, driven primarily by internal watch components, using energy and timing supplied by the clock.

The Extraordinary Effort behind the Breguet Sympathique No. 1 by THA

In 1989, Techniques Horlogères Appliquées (THA) was founded by François-Paul Journe, Denis Flageollet, and Dominique Mouret. Shortly after, they were commissioned by Breguet to recreate the Sympathique clock as a limited edition of 20 pieces. These modern Sympathique clocks were groundbreaking in themselves, marking the first time the mechanism had been adapted to wind and set wristwatches rather than pocket watches.

The first completed example, Breguet Sympathique No. 1, was unveiled at Antiquorum’s “Art of Breguet” exhibition and auction in Geneva on April 14, 1991, where it achieved a remarkable CHF 1,546,250. Over three decades later and on the 250th anniversary of Breguet, it will make its second appearance this weekend at Phillips in Geneva.

- Breguet Sympathique N°1

- The first time the concept of the Sympathique has been applied to a wristwatch (Images: Phillips)

The clock was built to the highest specifications in the pursuit of precision. It employs a five-second remontoir in the going train to ensure constant torque to a detent escapement, which delivers direct impulse to a Guillaume balance fitted with double cylindrical gold hairsprings. The movement offers an eight-day power reserve, wound by a crank at the base of the clock. A power reserve indicator, positioned at the top of the base, displays the state of wind. The dial displays a calendar with date on the left, day of the week on the right, and sectors above for the equation of time and a thermometer. A moon phase is positioned at the rear, visible just behind the wristwatch docking compartment. Once the wristwatch is docked, the clock winds and sets the minute hand of the watch every two hours.

At the time, Denis Flageollet was the Technical Director of THA, while Dominique Mouret oversaw workshop setup and supplier coordination. Flageollet is rare among his peers in that he is both a trained watchmaker and an engineer. His education in watchmaking was complemented by studies in micromechanics, giving him a rigorous grounding in both traditional horological craft and applied mechanical engineering. This dual expertise allowed him to approach watchmaking with both the sensitivity of an artisan and the analytical mindset of an inventor, enabling him to design mechanisms from first principles when needed, as the modern Sympathique unquestionably demanded.

He recalls the monumental effort behind the project in vivid detail: “I personally designed and built all of the clock’s mechanical components and systems, and adjusted the gold parts to assemble the clock cabinet alongside THA’s watchmakers, Pierre-André Grimm and Vianney Halter. One of our main challenges with the clock was perfecting the cover that closes over the watch.”

Flageollet continues, “The watch was based on a Lémania tourbillon movement that we thoroughly modified. For the watch movement, we faced a major challenge: it was the first time the Sympathique system had been adapted to a wristwatch with hour-setting and winding functions. I can’t remember how many prototypes of the winding crown I made before finally achieving a reliable winding function. Together with the watchmakers, we kept reworking the watch’s levers and the adjustment mustache to get everything operating smoothly. For the clock, we also had to remake the triggering cam and the hour adjustment lever spring several times before achieving consistent, reliable performance”

Asked whether AutoCAD played a role, Flageollet clarified that much of the early work predated its use: “We didn’t have CAD at the time. The initial drawings were done by hand by my draftsman back then, Ludovic Mutrux. Later we acquired our first 2D software, Autosketch, but it only allowed us to create isolated component drawings. Eventually, with the arrival of AutoCAD, we were able to produce more refined 2D drawings, and we used that software to finalize the plans for the series of brass Sympathique clocks for Breguet.”

“At the time, 3D design was just starting to be used in aerospace. We eventually purchased EUCLID – I believe I was the first watchmaker to use 3D software – but we never used it for the Sympathique clocks, which we designed entirely by traditional methods. Computers and printers at the time simply weren’t accurate enough to produce the 1:100 scale drawings we needed to get the gear teeth just right and achieve perfect gear meshing. So I built two compasses, each several meters long, and fixed them to the floor to draw everything out at full scale. For example, when scaled up 100 times, a centre-to-centre distance of 40 mm between two wheels becomes 4 meters – which is why we had to lay out these giant drawings directly on the workshop floor.”

The wheel train with a blade spring remontoir in the Breguet Sympathique No. 1, designed by Denis Flageollet. (Image: Denis Flageollet)

Another major challenge was creating the Guillaume brass and invar bimetallic balance for the clock. “We had to cast brass around invar, but at first it didn’t work because we kept getting air bubbles – we really needed a centrifuge. Then I came up with the idea of taking the mold straight from the furnace, placing it in a stainless steel bucket attached to the end of a rope, and spinning it above my head on the workshop roof. That ‘centrifuge’ is what we used to get the bubbles out of the molten material.”

“We also developed a special technique for making the cylindrical gold hairsprings. Together with THA’s mechanics, Pierre-Alain Gerber and Francis Joseph, we built a cylindrical frame that could be disassembled like a 3D puzzle. This let us shape the cylindrical hairsprings with the correct curves at both the collet and the stud. As with the balance wheel, it took lots of trial and error before we were able to thermally stabilize the hairsprings.”

“I could write a book about it – about all the technical challenges, but also about the people and the teamwork. It was a real journey,” says Flageollet. He recalls an amusing anecdote involving the detent for the clock’s escapement, “It was probably the first detent ever made using electrical discharge machining. I worked with the EDM guru at the time, Christian Biedermann, and the part he sent me was perfectly executed – except for one thing: what he did was produce a symmetrical rendition of my design – in other words, a mirror image, which made it totally unusable! With all the 2D views we’d sent back and forth, there was a mix-up. In hindsight, probably inevitable. I still have the inverted piece [see photo].”

A perfectly machined but entirely unusable mirror image of the detent, which Denis kept as a wry memento of the monumental project

“In the end, I pulled an all-nighter to re-machine the detent on a milling machine in our workshop, then hardened and tempered it on the spot. Vianney Halter came in early the next morning to hand-finish it, and that afternoon Pierre-André Grimm got the escapement working. It was 4pm when the clock started ticking for the first time. I came back to the workshop that night at 2am to make sure everything was still running. It was. I was totally exhausted and over the moon, and I have to admit, it brought a tear to my eye.”

It’s hard to hear Flageollet’s account without feeling both awe and a lump in the throat, at the ingenuity and also at the level of improvisation, teamwork and sheer force of will that carried it through. Horological merit is certainly measured by the final result, the achievement it represents, the ingenuity it reflects. But the story is inseparable from the struggle. The Breguet Sympathique No. 1 was wrestled into existence in the face of obstacles that would have derailed even the most seasoned workshop. It is about sleepless nights, bruised fingers, hand-drawn full-scale plans, a detent remade at dawn and a man spinning molten metal above his head on a rooftop because no other way would do. The brilliance of the modern Sympathique lies not only in what it does, but in what it demanded from those who made it.

The Breguet Sympathique No. 1 will be offered at The Geneva Watch Auction: XXI taking place on 10–11 May.

Breguet