Audemars Piguet Concludes RD Series With Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5

News

Audemars Piguet Concludes RD Series With Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5

Summary

On October 1, 2025, Audemars Piguet released the latest chapter in its 150th anniversary celebrations with a creation that feels less like a commemoration and more like a manifesto. The Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5 is not another incremental addition to AP’s canon of complications. It is a watch that dares to rethink a complication that has remained largely unchanged for more than two centuries: the chronograph.

Where the Royal Oak Concept Laptimer Michael Schumacher of 2015 or the Code 11.59 RD#4 of 2023 demonstrated Audemars Piguet’s virtuosity in layering functions, the RD#5 takes a different path. Its five years of development were not guided by the desire to squeeze more into less space, but by a deceptively simple question: “What should it feel like to use a chronograph today?” The answer is found in the all-new Calibre 8100, a patented movement that does not merely refine the mechanics of the chronograph, but re-engineers them from a blank page to deliver a sensation of control closer to a smartphone than a typical 21st-century tool watch.

- RD #1 Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

- RD #1 Royal Oak Selfwinding Perpetual Calendar Ultra-Thin

- RD #3 Royal Oak Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Extra-Thin 37mm in the plum Petite Tapisserie dial

- RD #4 Code 11.59 by Audemars Piguet Universelle

As Ilaria Resta, Audemars Piguet’s CEO, explains: “Audemars Piguet has always embraced a challenge. With our latest innovation — the RD#5 — the aim was to offer enthusiasts a complicated watch that is both comfortable and easy to use. Ultimately, a timepiece suited for today’s lifestyle that pays homage to the original ‘Jumbo’ with its aesthetic simplicity. The tremendous work carried out by our teams reflects the collective strength that has defined our brand for 150 years.”

From Supersonnerie to RD#5

Since 2015, Audemars Piguet’s R&D division has released a series of experimental prototypes under the RD label. Each has sought to resolve a structural problem that had dogged haute horlogerie for generations. RD#1 reinvented acoustic performance with Supersonnerie gongs and cases. RD#2 collapsed the layers of the perpetual calendar on a single plane to achieve an unprecedented slimness. RD#3, launched for the Royal Oak’s 50th anniversary in 2022, simultaneously delivered a high-amplitude escapement with a flying tourbillon in both a 37mm and 39mm case, resulting in the thinnest selfwinding flying tourbillon ever housed in a Jumbo case. And the RD#4 from 2023, the most complicated wristwatch ever produced by the brand, is a masterclass in combining multiple layers of complications without sacrificing ergonomics.

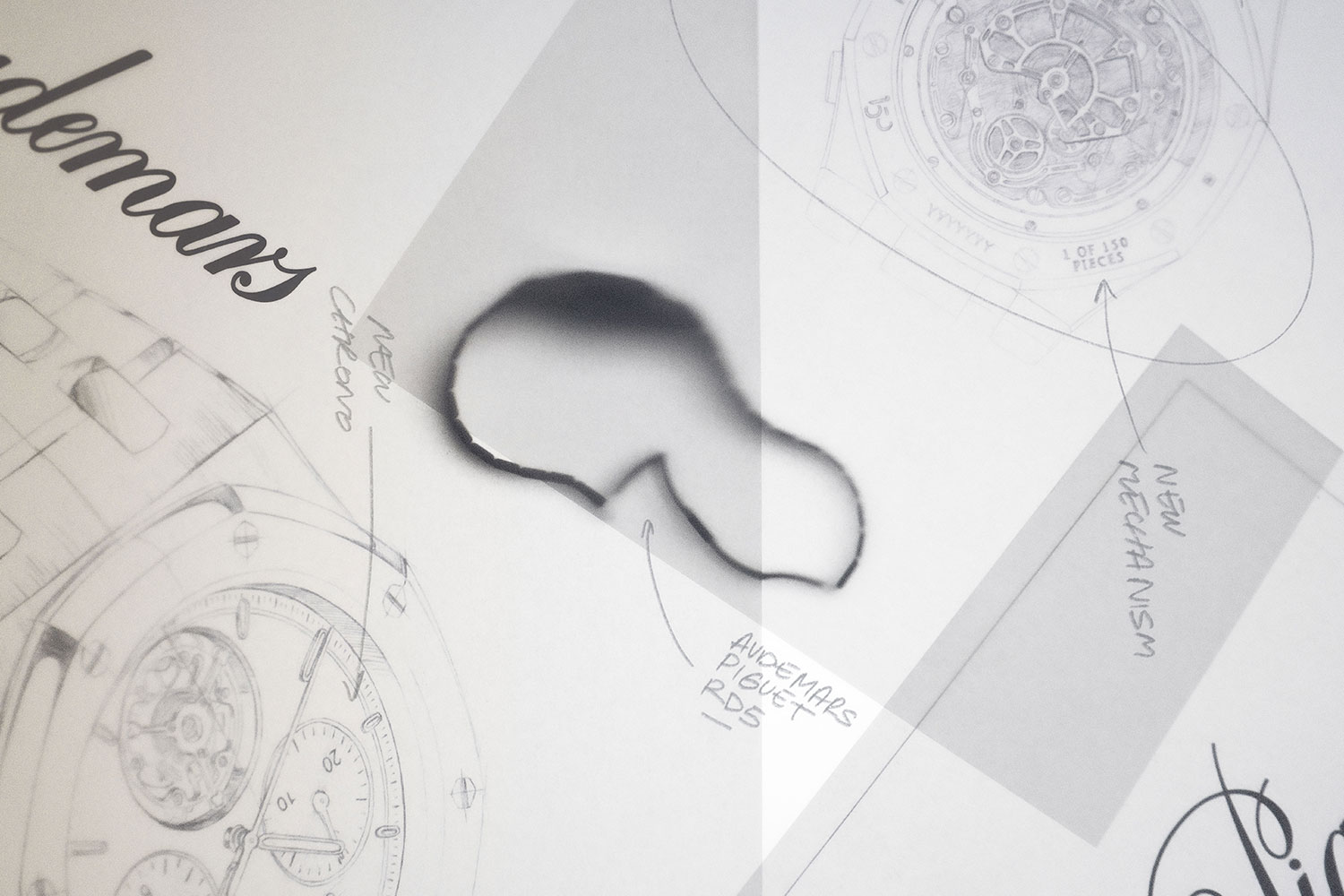

Conceived with mechanical elegance and refined simplicity in mind, the RD#5 seamlessly blends the iconic design of the Royal Oak “Jumbo” with high-performance technical sophistication. © Courtesy of Audemars Piguet

The chronograph, however, remained curiously untouched. For all the diversity of formats — monopusher, flyback, split-seconds — the underlying architecture of heart cams, hammers and friction springs had remained essentially unchanged since the 19th century. “Since the invention of the chronograph, everyone has done the same,” says Lucas Raggi, Chief Industrial Officer of Audemars Piguet, who has overseen the RD programme since its inception. “With RD#5, we reversed the problem. Instead of accepting the mechanical result and asking clients to adapt, we designed from the sensation of the client first.”

The project began with a simple observation. Chronograph pushers used to feel supple — particularly in the 1950s and 60s, when fine adjustment by watchmakers gave them a satisfying softness. But the arrival of water-resistant gaskets and the drive for mass production hardened their action. On a modern Royal Oak Offshore, for example, activating the chronograph typically requires around 1.2 newtons of force. The pushers travel more than a millimetre and feel stiff under the finger.

From the outset, the #RD5 project was led by a desire to create a chronograph that offers an elevated level of comfort

By contrast, the RD#5 reduces the necessary force by roughly a factor of five. The travel of the pushers is shorter, the engagement lighter, the feedback more controlled. “We asked ourselves what it should feel like to activate a chronograph in today’s world,” recalls Raggi. “The inspiration came from smartphones. You can control the sensation of a button; you decide the resistance, the length of travel, the click. We set a target sensation first and built the mechanism to deliver it.”

Giulio Papi, Director of Watchmaking Design at Audemars Piguet, and one of the most respected complications specialists of his generation, frames it in numbers: “Their travel — that is the distance they must be pressed — is often 1mm or more and requires a force of around 1.5 kilograms. Our aim was to reduce these values to enhance the client experience, drawing inspiration from smartphone buttons which typically have a travel of 0.3mm and require 300 grams of force.”

That analogy is not simply rhetorical. Achieving it required a complete redesign of the chronograph’s geometry. As Raggi explains: “We didn’t just make smaller pushers. If you do that on a normal movement, you’ll hit the case before the mechanism is engaged. The only way to achieve this was to reconfigure the mechanics themselves.”

How does the RD#5 improve chronograph pushers and crown design?

The rethinking of ergonomics did not stop at the pushers. The RD#5 also introduces a novel crown function selector. Instead of pulling the crown into different positions — a legacy of pocket watches ill-suited to modern ergonomics — the wearer simply presses its center. A discreet red stripe appears to confirm that the watch is in time-setting mode. Press again, and the crown returns to winding mode.

Flanking the crown, the RD#5’s push-pieces offer tactile comfort inspired by smartphone ergonomics. © Courtesy of Audemars Piguet

“It’s about user-friendliness,” says Raggi. “We didn’t want to stop with the pushers. Pulling a crown is always difficult, especially with short nails. So we integrated a selector push-piece. It respects the Royal Oak’s design codes but makes the experience effortless.”

This attention to the client’s tactile experience is part of what distinguishes RD#5. It is not just a technical tour de force; it is a philosophical statement that the era of designing complications for their own sake is over.

Calibre 8100: The “elastic chronograph”

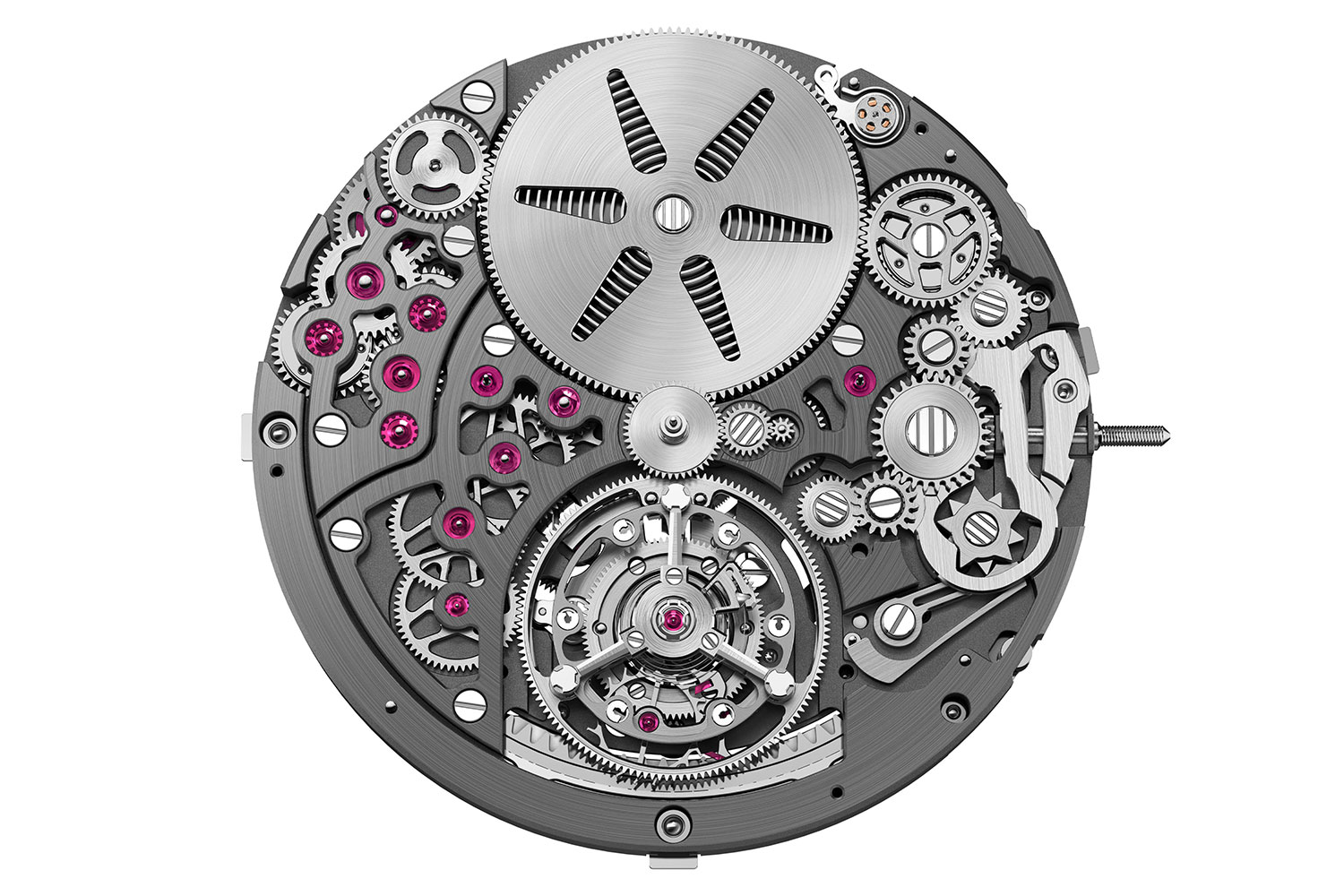

At the heart of RD#5 is the new Calibre 8100. At first glance, its counters at three and nine o’clock, its column wheel and its flying tourbillon at six seem familiar enough. But beneath the dial lies a mechanism that abandons the hammer-and-heart architecture that has defined chronographs for two centuries.

There are three types of behaviour for minute hands: trailing (slow progression), semi-instantaneous (slight advance then jump), and instantaneous jump (quick increment at the end of the second hand’s round)

In a traditional chronograph, the reset operation works by brute force. When the reset pusher is pressed, a hammer falls onto a heart-shaped cam fixed to each chronograph wheel. The energy required to overcome friction and inertia comes entirely from the user’s finger. It works, but it is crude: high forces, visible shudder, and wasted energy in the form of friction.

The RD#5 replaces this with a patented rack-and-pinion system that stores energy during the running of the chronograph. When reset is activated, that stored energy is released in an instant, driving the hands back to zero with minimal effort from the wearer. The difference is profound.

“Think of the traditional chronograph as a car driving with the handbrake on,” says Papi. “With Calibre 8100, the handbrake is gone, and the car is now tied to an elastic band. The energy that used to be lost as friction is now stored. When you reset, the elastic brings it back to zero in less than 0.15 seconds.”

This change of architecture yields multiple benefits. The reset is smoother, with no visible shudder. The energy demand on the wearer is reduced to a minimum. And because the energy is managed more intelligently, the mechanism can support an instantaneous minute jump — a feature highly prized by chronograph connoisseurs. Instead of the minute hand creeping forward or advancing semi-instantaneously, it snaps forward at the precise moment the seconds hand completes its sweep.

For resetting, a patented system stores energy until it reaches a tipping point, then releases it all at once, ensuring the hands return to zero quickly and with precision

Titanium components — most notably the chronograph wheels and even the hands — help to reduce inertia and allow this ultra-fast reset. The result is a system that consumes a similar amount of energy overall, but stores rather than dissipates it, delivering precision and smoothness never before seen in a chronograph.

The Calibre 8100 also rethinks the clutch system. Traditional vertical clutches rely on stacks of components and multiple springs, which increase complexity and thickness. AP’s solution is a pinion that moves vertically to engage or disengage, combining the advantages of a lateral clutch with the precision of a vertical one. The benefit is clear: no unwanted jump of the chronograph seconds hand when starting, combined with thinner architecture and greater reliability.

Fitted with a peripheral oscillating weight in platinum, Calibre 8100 reveals the beauty of its mechanism enhanced by refined finishing such as hand-beveling and satin brushing. © Courtesy of Audemars Piguet

The movement is driven by a column wheel for crisp control of start, stop and reset, and delivers a robust 72-hour power reserve at a frequency of 21,600vph (3 Hz). On the back, a platinum peripheral oscillating weight circles the caliber, reducing thickness while providing an unobstructed view of the bridges, bevels and satin finishes.

Why include a flying tourbillon in the RD#5?

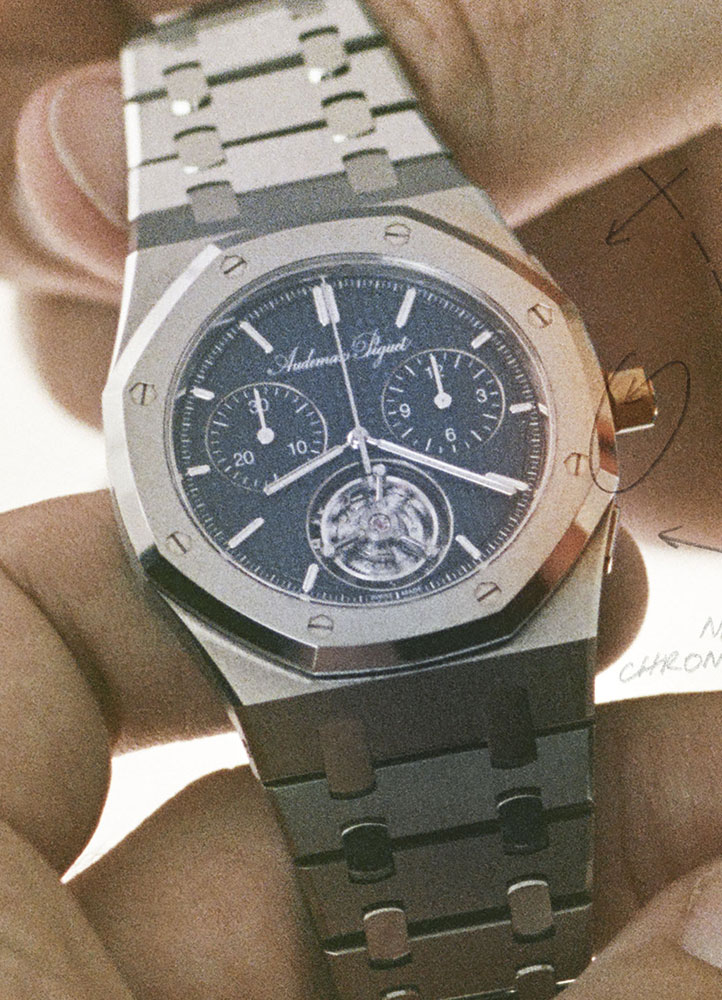

If the caliber represents a revolution, the case is a reminder of tradition. For the first time in its history, the Royal Oak Jumbo houses both a chronograph and a flying tourbillon. Maintaining the iconic 39mm diameter and 8.1mm thickness was non-negotiable, which made the engineers’ task all the harder. “Sometimes we are a little crazy,” smiles Raggi. “We said, let’s see if we can put everything into the Jumbo case. In the end, we did.”

For the first time in its 50-year history, the Royal Oak “Jumbo” is equipped with both a selfwinding chronograph and a flying tourbillon

To preserve the slim profile, Audemars Piguet adopted a double “glass box” sapphire crystal system. Flat on the outside but hollowed on the inside, the crystals above the dial and below the movement provide extra space for the rotation of hands and the oscillating weight without altering external proportions. The result is a watch that wears like a classic Jumbo, yet conceals a dual complication within.

The case and bracelet are crafted primarily from titanium, with the bezel, pushers, crown selector and studs in bulk metallic glass (BMG). First used in a Royal Oak Jumbo for Only Watch 2021, BMG is an amorphous palladium-rich alloy that combines high strength and corrosion resistance with a distinctive brilliance.

While completely flat on the outside, the “glass box” on both the dial and caseback are hollowed on the inside to create additional space for the rotation of the hands as well as for the movement and its oscillating weight

Discovered in the 1960s, bulk metallic glasses are metals cooled so quickly that their atoms cannot form a crystalline structure. The result is a material as strong as steel yet capable of a glass-like polish. In RD#5, BMG’s mirror-finished bezel and pushers provide a striking contrast to the satin-brushed titanium case and bracelet, whose polished bevels create the signature Royal Oak play of light.

The dial is a study in understatement. The “Bleu Nuit, Nuage 50” Petite Tapisserie pattern — famously developed for the first Royal Oak in 1972 — is paired with snailed counters in matching blue. The chronograph hands are titanium for lightness, while white-gold hour markers and hands are rhodium-toned for maximum legibility. At twelve o’clock sits a special Audemars Piguet signature drawn from archival designs, marking the 150th anniversary. The caseback, engraved “1 of 150 pieces” and “150 Years,” underscores the rarity of this edition.

The signature Petite Tapisserie dial in “Bleu Nuit, Nuage 50” is highlighted by rhodium-toned gold hour markers and luminescent hands in 18-carat white gold; the counters at 3 and 9 o’clock are rendered in the same blue with a snailed finish for enhanced legibility

The chronograph is not the RD#5’s only feat. The watch also integrates the high-amplitude flying tourbillon first seen in RD#3. Redesigned in 2022 to be thinner while maintaining its proportions, this tourbillon uses a peripheral drive system that allows higher balance amplitudes and improved energy distribution. By combining it with the new chronograph calibre, AP has created a dual complication unprecedented in the history of the Jumbo.

Raggi admits the tourbillon was not strictly necessary for the chronograph project. “It would have been simpler without,” he concedes. “But when you are making a small run of exceptional pieces, you want to raise the challenge. It felt right to include it.”

The chronograph is often taken for granted in modern watchmaking, but it remains among the most technically demanding complications. Components move at high speeds, tolerances are unforgiving, and physical phenomena like inertia and friction constantly threaten precision. That is why, although AP has produced chronograph wristwatches since the 1930s, the manufacture has only rarely attempted to reinvent their architecture.

Papi puts it plainly: “The chronograph is probably the most difficult complication to produce. Because it has been industrialized, people think it is easy. But to rework it from the start, to redesign the way it functions, is harder than making a minute repeater.”

By addressing the chronograph’s fundamental weaknesses — forceful pushers, wasted energy, shuddering resets — RD#5 places Audemars Piguet at the forefront of a field that has seen little true innovation in two centuries.

What does the RD#5 mean for the future of Audemars Piguet chronographs?

Only 150 examples of RD#5 will be produced, but its innovations are not intended to remain unique. As Raggi explains: “We are still learning from RD#5, but it has so many advantages that we are determined to expand it into more regular production. It will come, step by step.”

Marking the brand’s 150th anniversary, the dial bears a special Audemars Piguet signature inspired by archival designs at the 12 o’clock position

Patents protect the specific mechanisms, but the broader philosophy — designing complications around user sensation rather than mechanical convention — may well set a precedent others will follow. “The theory of making a more user-friendly product will be followed for sure,” Raggi acknowledges. “This is just the beginning of a new era for watchmaking.”

The Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5 is not merely a celebratory anniversary piece. It is a redefinition of what a chronograph can be in the 21st century: tactile, intuitive, elegant, and ergonomically precise. By rewriting the chronograph’s architecture from the ground up, Audemars Piguet has made it feel as natural as tapping a smartphone, without compromising the visual and horological codes of the Jumbo.

In doing so, the Manufacture has not only honoured its 150-year legacy but also set the stage for the next century. The beat goes on, but now the rhythm is smoother, lighter, and unmistakably more human.

Tech Specs: Audemars Piguet Royal Oak “Jumbo” Extra-Thin Selfwinding Flying Tourbillon Chronograph RD#5 150th Anniversary 39mm

Movement: Selfwinding Caliber 8100; 31.4mm (14 lignes) diameter; 4mm thick; 379 components; 44 jewels; minimum power reserve of 72 hours; 3 Hz (21,600 vph); patented rack-and-pinion reset system

Functions: Hours and minutes; flyback chronograph with hour counter; instantaneous minute jump

Case: 39mm × 8.1mm; titanium, bulk metallic glass (BMG) bezel, push-pieces and function selector chip; glareproof sapphire crystal; BMG and sapphire caseback; titanium and BMG crown; water-resistant to 20m

Dial: Petite Tapisserie dial in “Bleu Nuit, Nuage 50”; rhodium-toned 18-carat pink gold bathtub hour-markers; 18-carat white gold hands with luminescent material; blue counters with snailed finish; rhodium-toned inner bezel

Strap: Titanium and BMG bracelet with titanium AP folding clasp

Audemars Piguet