A Retrospective: The Legacy of Urban Jürgensen

Reference

A Retrospective: The Legacy of Urban Jürgensen

The history of Urban Jürgensen is less a linear tale than a legacy shaped primarily by three acts. The first is by the man himself; Urban Jurgensen was a horologist and academic whose scientific approach set a new standard for 19th-century watchmaking outside the established centers of watchmaking power. Then, over a century later, Peter Baumberger and the great English watchmaker Derek Pratt restored the name through uncompromising craft at a time when such values had all but disappeared. The third act, which is about to begin next week, is enacted by the father-and-son team, Andy and Alex Rosenfield, working with Kari Voutilainen, with its first three watches soon to debut. In anticipation of this next chapter, it’s worth revisiting the origins and the arc of the story so far.

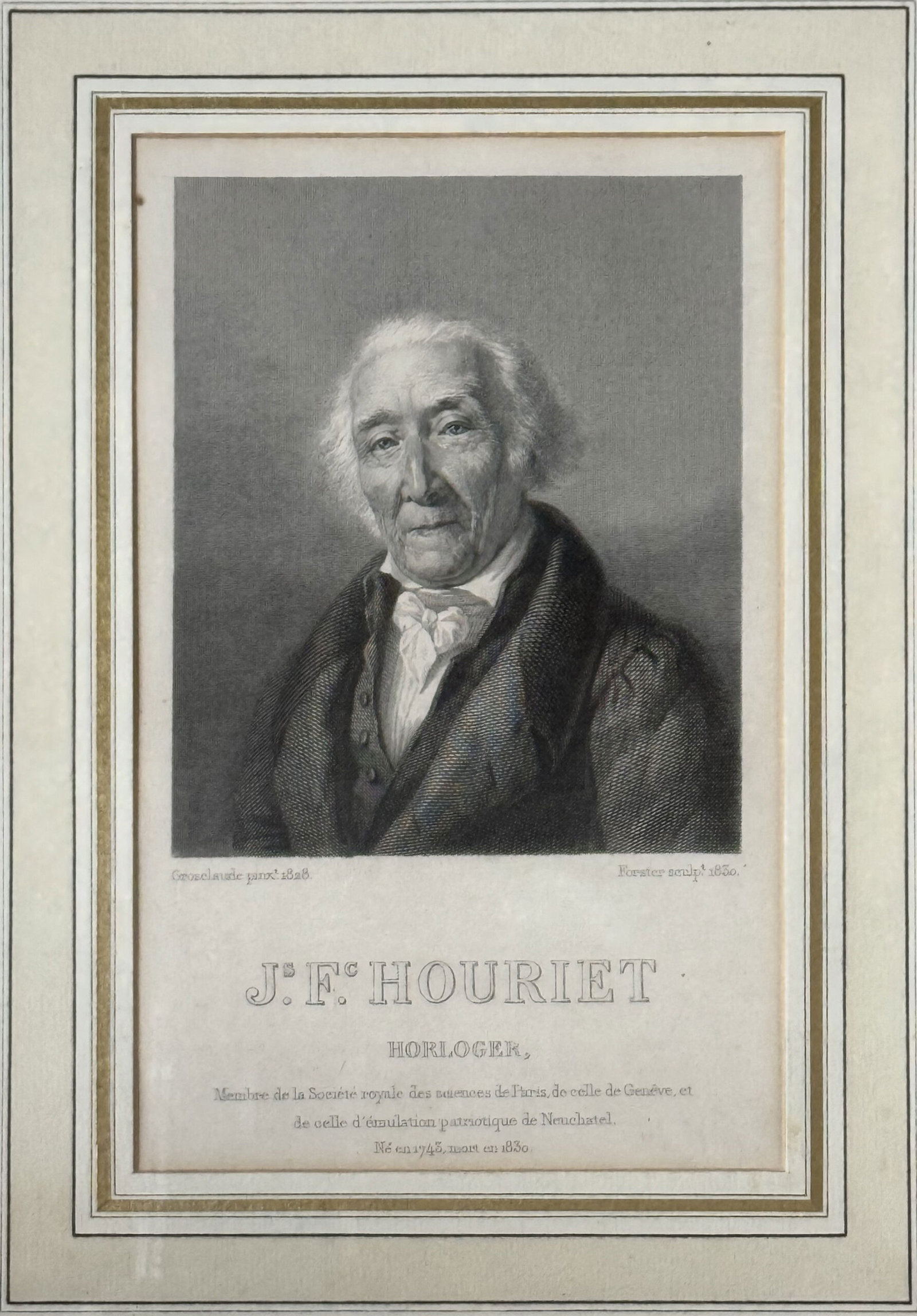

The Jürgensen family’s involvement in watchmaking began as early as the mid-18th century with Jørgen Jørgensen, born in Copenhagen in 1745. At the age of 14, he apprenticed under Johan Jacob Lincke, a prominent Copenhagen watchmaker. In 1766, Jørgensen traveled to Germany for further training, during which he adopted the Germanic spelling of his name, becoming Jürgen Jürgensen. He later moved to Le Locle, Switzerland, where he worked under Jacques-Frédéric Houriet, a chronometer maker and tireless researcher, best known for inventing the spherical hairspring. This experience exposed Jürgensen to advanced watchmaking techniques and the early stages of systemization in watchmaking. When he returned to Copenhagen in 1772, he brought not only technical knowledge but a vision.

The following year, he applied to the Copenhagen Watchmakers’ Guild for permission to produce a repeating watch as his guild masterpiece, partnering with Isaac Larpent for its execution. That collaboration would evolve into something larger. In 1781, he received formal permission to establish a workshop under his own name. The resulting firm, Larpent & Jürgensen, produced around 4,000 watches between 1773 and 1814, marking Denmark’s first sustained effort in serial watch production. But it was his eldest son, Urban, born in 1776, who would elevate the family’s reputation beyond the national industry to the highest ideals of European horology.

A Danish Watchmaker on the World Stage

Born in Copenhagen in 1776, Urban Jürgensen belonged to a generation of watchmakers who blended scientific theory with craft, applying the principles of physics and metallurgy to improve chronometry. He was also capable of producing marine chronometers.

An 18th–19th century portrait of Urban Jürgensen, the pioneering Danish horologist whose legacy continues to shape precision watchmaking today.

His work was influenced by his time studying under the leading lights of 18th-century horology, placing him in the broader European Enlightenment tradition where watchmaking became increasingly codified through scientific inquiry. He was trained from an early age in his father’s workshop before embarking on a tour that would take him across the intellectual centers of European watchmaking.

In 1797, he was sent to Le Locle to apprentice under his father’s friend, Jacques-Frédéric Houriet, who would later become his father-in-law. From there, he continued to Geneva to study with Marc-Auguste Pictet, a physicist, meteorologist and astronomer known for his experimental work and influence across the sciences.

Urban Jürgensen later journeyed to Paris, where he trained under Ferdinand Berthoud and Abraham-Louis Breguet, absorbing both the rigor of scientific horology and the flair for mechanical invention. But it was his interest in chronometry that would come to define him, and for that, he turned to London, where he studied with John Arnold and John Brockbank, the foremost English chronometer makers of the era. By the time he returned to Copenhagen in 1801, Jürgensen had absorbed the best of Swiss, French and English watchmaking.

Back at home, Urban Jürgensen found himself at the center of a national ambition to establish domestic production of marine chronometers, given the increasing demand for precision timekeeping in navigation. But bound by filial duty and the weight of legacy, Urban set aside the government’s proposal and rejoined the family workshop.

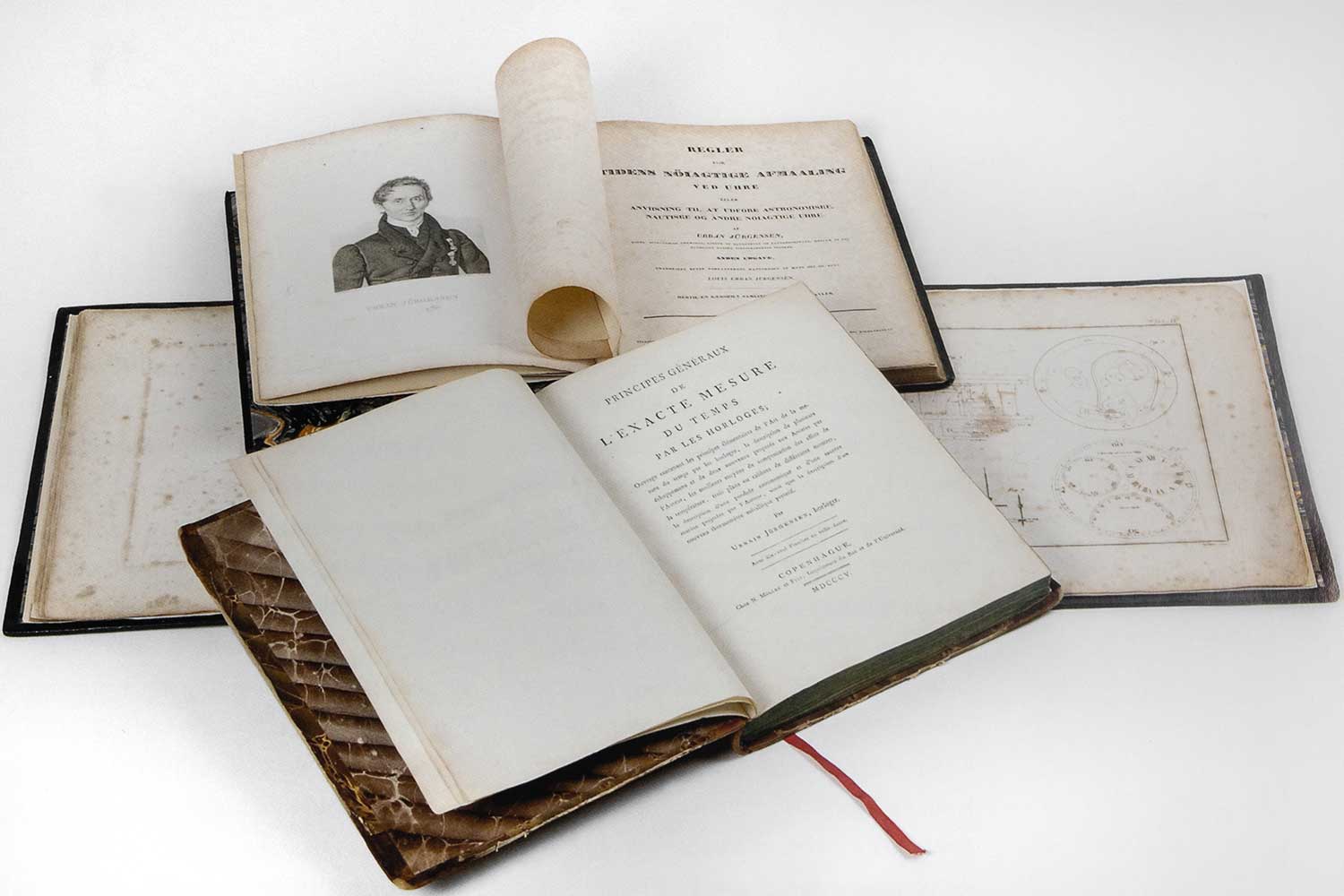

In 1804, he published a textbook on watchmaking — the first book on watchmaking to ever be written in Danish — and received a silver medal from the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences for his treatise on the manufacture and hardening of steel springs. The following year, he was awarded a gold medal by the Royal Danish Agricultural Society for his work on bimetallic thermometers. In 1807, Urban Jürgensen returned to Switzerland to visit his father-in-law, Jacques-Frédéric Houriet. There he developed machinery intended to bring his father’s Copenhagen workshop into line with the most advanced standards of continental watchmaking. When he finally returned to Denmark, he did not come alone. With him were three Swiss watchmakers, all funded by the Danish government.

The book Regler for Tidens nöiagtige afmaaling ved Uhre published in 1804 was the first book on watchmaking to ever be written in Danish.

By 1811, he had established his own workshop in Copenhagen and presented his first marine chronometer, launching what would become a successful period of serial production. Over the next two decades, he produced more than 700 watches, 45 marine chronometers and six precision pendulum clocks.

Urban Jürgensen’s relationship with King Frederik VI of Denmark was instrumental in establishing his reputation as a master horologist. The king granted Jürgensen a royal appointment to supply the Danish court with watches and the Admiralty with chronometers.

One of the most notable commissions was the creation of a luxurious marine chronometer, known as the “Krusenstern” chronometer. This timepiece was presented in 1821 to Russian naval officer and explorer Baron von Krusenstern. It exemplified the pinnacle of precision and craftsmanship of the era, featuring a cylindrical hairspring and an Arnold spring detent escapement along with a fusée-and-chain transmission.

The Urban Jürgensen No. XI “Krusenstern” chronometer, crafted in rose gold circa 1812. Commissioned for the famed explorer Adam Johann von Krusenstern, the timepiece exemplifies the precision and elegance of early 19th-century horology. (Image: Antiquorum)

In 1810, he was awarded the prestigious Order of the Dannebrog by King Frederik VI, recognizing his advancements in watchmaking. Furthermore, in 1815, he became the first watchmaker to be admitted to the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, reflecting his commitment to integrating scientific principles into horology.

Through these honors, Urban Jürgensen solidified his status as a pivotal figure in the advancement of precision timekeeping in Denmark and beyond. His workshop also produced fine pocket watches, many of which were destined for export, particularly to the growing American market. Despite personal tragedy, having lost five of his eight children, Urban remained committed to his craft until his death in 1830. His legacy was carried on by his sons, notably Louis Urban and Jules Frederik, under the name Urban Jürgensen & Sønner.

After Urban’s death in 1830, his sons Louis Urban and Jules Frederik continued the business under the new name Urban Jürgensen & Sønner. Louis Urban remained in Copenhagen, producing chronometers and pocket watches in limited numbers, while Jules established a workshop in Le Locle, which would later grow into one of the most commercially successful arms of the family.

A Jules Jürgensen pocket watch with its movement exposed, highlighting the precision mechanics of 19th-century horology. (Image: Revolution©)

Although the fourth generation showed promise, particularly Urban August Jürgensen, who died prematurely in 1866, the Danish line gradually declined. By the end of the 19th century, management had passed into the hands of non-family successors and the Danish branch served mainly as a repair center, distributor and museum.

Meanwhile, the Swiss side of the family, especially Jacques Alfred Jürgensen, maintained production into the late 19th century, selling watches under the Jules Jürgensen name to clients including Tiffany & Co. in New York. After Jacques Alfred’s death in 1912, the family’s involvement came to an end. The brand passed through various owners, and by the mid-20th century, production had shifted to La Chaux-de-Fonds and later to the United States, with the resulting watches increasingly detached from their horological roots.

Peter Baumberger and Derek Pratt

Urban Jürgensen was eventually revived by Peter Baumberger, a distinguished collector and a trained watchmaker, who acquired the rights to Urban Jürgensen in 1979 and eventually the whole company in 1985. Born in 1939 in Koppigen, Switzerland, Baumberger came of age in a time when mechanical watchmaking still held pride of place, at least for a little while longer. He studied at the watchmaking school in Solothurn, the only institution in Switzerland that offered instruction in the Swiss-German dialect and graduated in 1959. By then, a new era of science and the technology had begun; early developments in quartz timekeeping were underway.

With jobs growing scarce, Baumberger joined his father’s firm, which produced luminous dials. The work was steady, if not especially romantic. Like many watchmakers of his generation, Baumberger carried a reverence for traditional watchmaking. When a former colleague invited him to join an antique clock business in exchange for a modest investment, he accepted without hesitation. It was a modest start, but one that would eventually set the course for everything that followed.

In 1976, during the bicentennial celebration of the Danish Watchmakers’ Guild, Baumberger was passing through Copenhagen when he came across the window of Urban Jürgensen. The shop, then owned by Christian Gundesen, had been transformed into a small archival display. Inside were tools, technical drawings and a selection of finely made timepieces from the past. Baumberger was met with polite skepticism. Every piece he asked about was said to be not for sale. He made one last attempt, asking about a precision pendulum regulator mounted on the wall. This time, the answer was different. It had already been reserved for an American collector and then, perhaps as a joke, the owner asked if he would like to buy the whole place.

The casual remark sparked the idea that the company might one day be his. In the ensuing years, he pursued that possibility. Meanwhile, Gundesen sold the business to his nephew, Gerhard Scheufens. When Baumberger finally approached him, he was told firmly that the name Urban Jürgensen would remain in Danish hands.

Baumberger’s deep understanding of horology and his admiration for the company’s history eventually made their case. He was able to demonstrate that he not only understood what the name meant, but also had the skills and vision to restore its standing. Eventually, with a little theatricality — namely a completed watch by Derek Pratt — he managed to win Scheufens over. With that, the second great chapter of Urban Jürgensen began.

Pratt, born in southeast London, had moved to Switzerland in 1965, where he established his own workshop in 1972. He began specializing in restoration work and became acquainted with Peter Baumberger. Pratt restored numerous historical pocket watches from Baumberger’s personal collection, including the most complicated Vacheron Constantin of the time, the grand complication No. 402833, made for King Fuad I of Egypt in 1929.

Pratt was a close friend and a trusted horological confidant to George Daniels. Like Daniels, he was one of the rare few capable of building an entire watch by hand from raw materials and his skill as an engine-turner was second to none.

Baumberger and Pratt’s revival of Urban Jürgensen began at a time when quartz had all but eclipsed mechanical watchmaking. While much of the Swiss Jura had gone silent, the pair worked as though in a vacuum, undeterred by the industry’s collapse. They made the most of the moment. As watchmaking houses shuttered, tools and machinery could be had for scrap, allowing the pair to equip a full atelier and resurrect the brand on their own terms.

An exquisite Urban Jürgensen tourbillon pocket watch crafted by the legendary Derek Pratt. Complete with power reserve indicator and subsidiary seconds, it exemplifies the revival of traditional complications through uncompromising artisanal watchmaking. (Image: Revolution©)

The finely finished tourbillon movement features twin barrels and a bimetallic compensation balance wheel (Revolution©)

They began with plans for a small series of exceptionally crafted tourbillon pocket watches, the most renowned of which was the Oval — a project Pratt began immediately after joining as technical director in 1982. Several of these tourbillon pocket watches featured Pratt’s distinctive cage-mounted remontoir, marking the first time a watchmaker had integrated a remontoir directly onto the tourbillon cage. By so doing and eliminating any intermediate wheels between the remontoir and the escape wheel, he sought to minimize fluctuations in torque delivery. In this setup, the mainspring drives the gear train and rotates the tourbillon cage, while the remontoir, periodically recharged by the gear train, delivers consistent force directly to the escapement and balance wheel.

Pratt took a particular interest in the Reuleaux triangle, a shape of constant width that, despite its triangular form, behaves like a circle, enabling it to rotate within a square or any other confining shape of matching width, without changing orientation. In the remontoir, it serves to convert rotary motion into linear motion, which controls the release of the stop wheel.

A closer look at Pratt’s signature cage-mounted remontoir in the Oval. The remontoir wheel and escape wheel are co-axially aligned. The Reuleaux triangle is made of synthetic ruby and revolves within a two-pronged fork that oscillates as the triangle rotates. This back-and-forth motion is mirrored by the remontoir anchor, to which the fork is attached. As the fork moves, the anchor unlocks one of the three teeth on the remontoir stop wheel. Each time the remontoir stop wheel, driven by the cage, snaps forward, it tensions the remontoir spring. The spring stores enough of energy to drive the escapement and thus the balance.

These watches represent the most important Urban Jürgensen creations of the era and are a reminder that great watchmaking is as much about the rare courage it takes to reimagine and push forward, as it is about upholding the past. Pratt also produced a series of complicated pocket watches using 19th century ébauches, often adding his own complications.

Urban Jürgensen & Sønner No. 3013, a minute repeating pocket watch with chronograph and perpetual calendar made by Derek Pratt

Urban Jürgensen eventually released a total of 11 wristwatch references, sequentially numbered from Ref. 1 to Ref. 11. Introduced in 1982, the Ref. 1 was a chronograph with a triple calendar and moonphase. It was based on the Zenith El Primero Caliber 3019 PHF and was produced in a limited run of 186 examples between 1982 and 1986.

Urban Jürgensen Ref. 1 , a chronograph with triple calendar and moon phase, based on the Zenith El Primero (Revolution©)

The pair launched the Ref. 2 in 1986 — a perpetual calendar built on the ultra thin Frédéric Piguet Caliber 71, a self-winding movement with an off-centered rotor. The same movement was used by Daniel Roth, first at Breguet and later at his own brand. A total of 50 pieces of the Ref. 2 were produced in platinum and 172 in gold.

Urban Jürgensen Ref. 2, a perpetual calendar made by Lemania, built on the ultra thin Frédéric Piguet Caliber 71 (Image: Antiquorum)

The Ref. 3 was introduced in 1993 and was distinguished from the Ref. 2 with the addition of a power reserve indicator, which required the integration of a differential gear to compare the relative motion between winding and unwinding, translating that into a consistent, bidirectional indication of the remaining power. On paper, the change seemed modest, but its execution proved unexpectedly demanding, consuming far more time and resources than anticipated.

The Urban Jürgensen Ref. 3 is a perpetual calendar with a power reserve indicator. Note the exceptionally fine guilloché work (Revolution©)

These references had solid silver, engine-turned dials that were finished with traditional Breguet frosting and precious metal cases with stepped bezels and individually soldered teardrop lugs. Though these, along with the remaining references, all relied on outsourced base movements, the groundwork for a proprietary caliber quietly began in 2003.

It was an exceptionally ambitious undertaking, not simply to create an in-house movement for prestige, but to build one that would honor the legacy of Urban Jürgensen. It resulted in the first wristwatch fitted with a pivoted detent escapement. Long used in marine chronometers and pocket watches, the detent escapement was prized for its precision under stable conditions due to its direct impulse system. However, it remained fundamentally unsuitable for the wrist due to its inherent sensitivity to shocks.

Pratt adapted a Unitas base caliber to test a detent escapement in a wristwatch setting. The results were promising, but the obstacles were considerable. Chief among them was the escapement’s lack of shock resistance. Being a single impulse escapement, which delivered impulse to the balance wheel only in one direction, it was an issue that loomed much larger in a wristwatch than a pocket watch and one that couldn’t be fully eliminated.

Pratt succeeded in building a working prototype but the real ambition was serial production. That would require not just watchmaking skill, but a high level of engineering. Thus, the technical development was eventually handed to a young engineer, Jean-François Mojon, who would later go on to found Chronode. The brief was made more complicated by the need to develop a base that could not only support complications but be configured with either a chronometer escapement (P8) or a traditional lever (P4).

As Pratt’s health began to decline, Kari Voutilainen stepped in. He oversaw its decoration, assembly, adjustment and testing, and provided critical feedback to Mojon’s team as the development progressed. The P8 and P4 were eventually launched, though only after the passing of both Pratt and Baumberger.

- Urban Jürgensen Ref. 11C

- The Caliber P8, the world’s first wristwatch with a detent escapement (Images: Phillips)

In 2011, following Peter Baumberger’s death, Urban Jürgensen was acquired by Dr. Helmut Crott, a noted collector and founder of the eponymous auction house, and later in 2014, it was sold to a consortium of Danish private investors led by Søren Jenry Petersen, a Danish engineer and former executive at Nokia. The period saw the release of several models, including the brand’s first sports watch, but these efforts did little to deepen its standing in the world of independent watchmaking.

The Rosenfield Family and Kari Voutilainen

In 2021, the Rosenfield Family acquired Urban Jürgensen. Andy Rosenfield, in addition to being the President of Guggenheim Partners, is one of the world’s most accomplished watch collectors with a highly attenuated passion for independent watchmaking. Amongst some of his favorite watches were his Urban Jürgensens. When he discovered the brand was for sale, he was immediately struck with a vision for its revival. Working with his son Alex, the two negotiated and acquired Urban Jürgensen on behalf of the Rosenfield Family. Andy is Chairman and Alex, who brings with him an important fresh perspective on branding, communication and sales from his years in media and fashion, is Co-CEO. Andy then approached his close friend and one of watchmaking’s most beloved figures, Kari Voutilainen, to inject his particular style of technically innovative and craft-based acumen as the other Co-CEO.

Says Voutilainen, “For me, returning to Urban Jürgensen feels like coming home. The brand played a crucial role in my early career. I was just getting started in watchmaking when Peter Baumberger saw potential in me and encouraged me to join him. It was truly an introduction to the art of fine watchmaking, particularly the distinctive finishing techniques that would shape my future work.”

Humble and quiet in demeanor, yet masterful across every discipline in watchmaking, these qualities belie the strategic mind that has quietly built one of the most not just vertically integrated, but also comprehensively equipped independent manufactures in the industry at his own business Voutilainen and his case, dial and engine turning factories, which he will continue to run separately from his role at Urban Jürgensen. In just two decades, Voutilainen has transformed his brand into a powerhouse, capable of producing everything from movements to dials, cases and hands, all to his exacting standards for his own watches, as well as for other independent brands. His name has quietly become a foundation for many fledgling brands, lending substance and credibility to those whose expertise often begins with design rather than execution.

Voutilainen’s association with Urban Jürgensen began in 1996, a time when he was still finding his footing as a watchmaker. He had presented his very first watch — the tourbillon pocket watch — at an exhibition in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Among those who took notice was Peter Baumberger, who was impressed enough to offer to buy the watch. Voutilainen declined to sell it, but the encounter marked the beginning of a relationship that would shape much of what followed.

Details of the new watches and the company’s plans remain under tight wraps until the launch on June 5, which is scheduled to take place in Los Angeles.

Says watch collector William Massena, “This launch represents the most impressive renaissance for any brand I’ve seen since 1994 when Günter Blümlein revived A. Lange & Söhne.”

With the Rosenfield family and Voutilainen now at the helm, the brand is once again in the hands of those who understand both its weight and the quiet authority in pushing every aspect of watchmaking to the highest level. The future seems limitless — as bright at the Californian sun.

This article was brought to you by Urban Jürgensen and Revolution.

Urban Jurgensen