A Guide to the Automatic Winding System

Technical

A Guide to the Automatic Winding System

The self-winding watch is something that we (mostly) take for granted these days. I have not actually run the numbers, but if I were a betting man, I would confidently state that the sales of automatic watches outnumber those of manually wound watches by a large margin. Interestingly, the automatic winding mechanism—consisting of the wheel train, bridges, and the self-winding rotor—does not actually fall within the accepted definition of a complication, which includes any function other than the indication of hours, minutes, and seconds. However, it is still considered one. The tourbillon is the only other complication that falls outside these established parameters. With the majority of watches being self-winding, we don’t often stop to think about how this feat is achieved.

The Magic Of Automatic

For a watch to function, it requires energy—energy that originates from you, the wearer. When you wind the crown of a manually wound watch, you transfer your energy into it by tightly coiling the mainspring around a component called the barrel arbor. As that spring becomes wound, it naturally seeks to unwind. When it does, the energy is transferred through a series of wheels, and the watch begins to tick. A self-winding watch does the same thing, but it has the option to receive that energy in a different way. It uses a free-spinning weight inside the watch—known as the self-winding rotor.

How does this self-winding rotor achieve its goal? As the wearer moves their arm throughout the day, the self-winding rotor spins like a merry-go-round at the fair. It does this using gravity and its own inertia. As it does so, the automatic mechanism coils the mainspring a little tighter with every spin of the rotor, thus winding the watch and allowing it to continue running without the need to use the crown.

It’s important to note that most automatic watch movements can also be manually wound and should be if the power has completely run down. The self-winding feature of most watches is more of a maintaining power, which needs a little kick to get going. The basic components of manually wound and automatic watch movements are similar in construction, with only a few key differences: the barrel and the mainspring.

The Mainspring

Have you ever heard someone say, ‘I overwound my watch’?” Well, they probably didn’t—especially if it was automatic. Here’s why: a manually wound watch, when fully wound, reaches a hard stop. The mainspring has reached its maximum tension, and you cannot turn that crown any further. Technically, the mainspring could snap if you really forced it, but you’d need the forearms of Popeye, and it’s a rarely seen phenomenon.

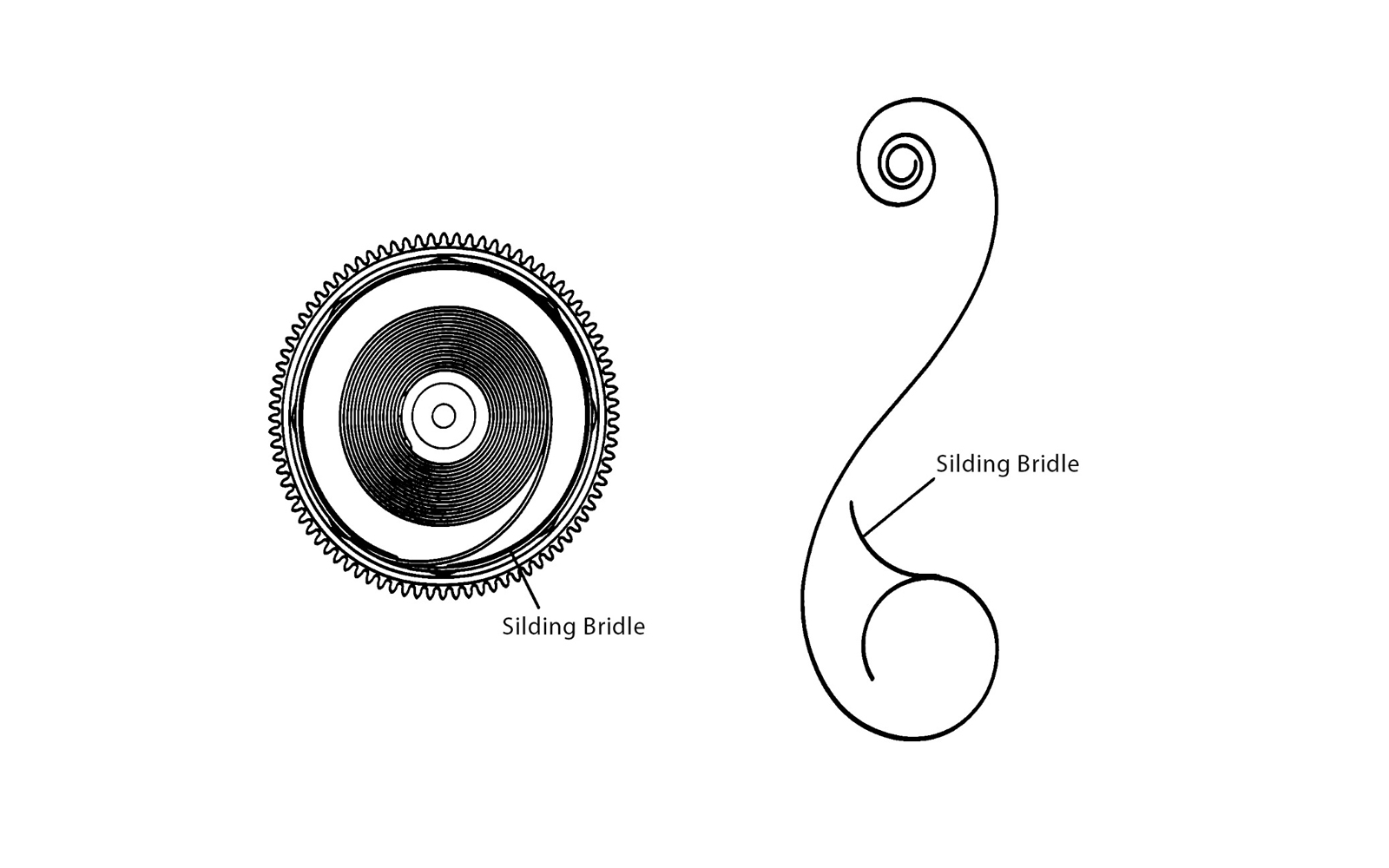

A self-winding watch, however, can be wound indefinitely without snapping the spring. The reason for this is that modern automatic mainsprings have a differently shaped end compared to their manual-wind counterparts. This design includes a ‘slipping bridle,’ in which the outer end of the mainspring has an additional length attached that splays in the opposite direction.

The Mainspring Barrel

Automatic and manually wound mainspring barrels look the same from the outside, but it’s what’s on the inside that counts. Both barrels have the mainspring coiled tightly inside, powering the watch as it slowly unwinds. The manual-wind barrel has a hook on the outer wall that locks the mainspring, preventing it from being wound any further once the maximum tension has been reached.

This contrasts with an automatic mainspring. The splayed end discussed earlier is curled back on itself when mounted inside the mainspring barrel. This gives the spring a strong grip on the barrel wall, meaning it does not require a hook or catch point. The force of this grip allows the spring to be wound to its maximum tension. If any additional energy is wound into the mainspring, the bridle loses its grip, and the spring slips around the barrel wall until the force evens out and the grip is reestablished.

With these two components working in harmony, the watch can be wound indefinitely without causing damage.

Modern Automatics – The Formative Years

Wristwatches originated in the early 20th century, as the public recognized the charm and practicality of a watch that no longer needed to be kept in a pocket. After Rolex submitted a wristwatch to the Kew Observatory for testing, and it became the first wristwatch to receive a Class A Precision Certificate, concerns about accuracy were cast aside, and public demand grew. By the 1930s, wristwatch sales had surpassed those of pocket watches and continued to rise in popularity. In the early years, wristwatches were exclusively manual wind, but that was about to change.

The Englishman

The modern automatic watch debuted to the public at the 1926 Basel Fair with the introduction of the Harwood watch. John Harwood, an English watchmaker, teamed up with Fortis to produce this new movement, known as a ‘bumper’ style of automatic winding, later popularized by Omega. Harwood wasn’t the first to produce a self-winding watch. Perellet, Breguet, and others were experimenting with self-winding movements as early as the 1700s, but Harwood was the first to mass-produce and bring it to the modern market in a wristwatch.

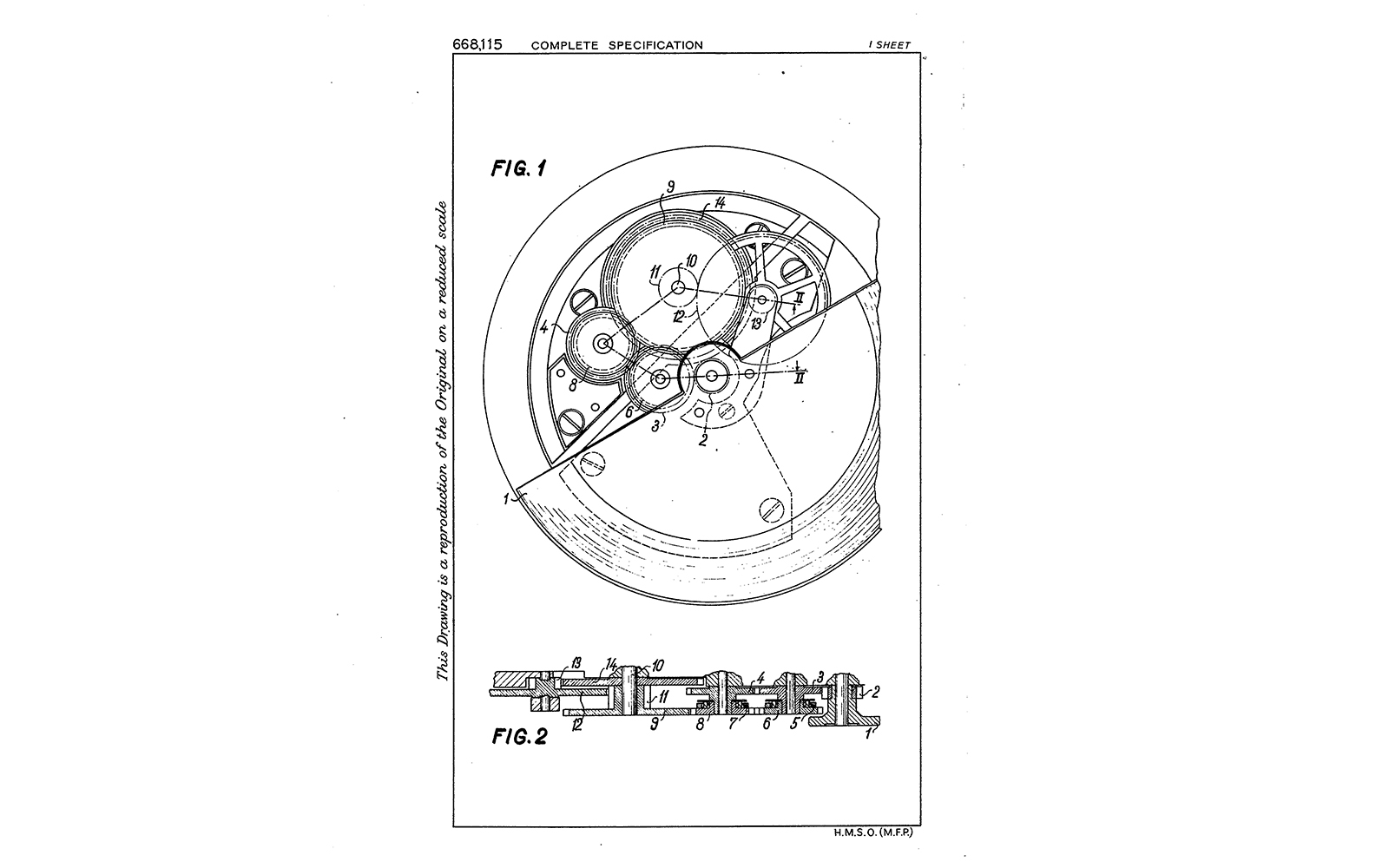

The first mass produced self-winding movement for a wristwatch was made by the English watchmaker John Harwood who patented his design in 1923. It was unidirectional winding system with a centrally mounted weight that oscillated through an arc of about 130 degrees, limited by bumpers at either end of its weight. (Image: The British Museum)

Harwood’s automatic movement did not feature a rotor that made a complete revolution, as seen in modern self-winding watches; instead, it had a weight limited to an arc of about 130 degrees. It also wound the watch only when travelling in one direction. When the motion of this weight reached its limit, a spring-loaded buffer inside causes it to ‘bump’ back—just like giving your friends whiplash on the dodgems as a kid.

Unfortunately, Harwood’s company lasted only a few years before going bankrupt—then the new kid on the block showed up: Rolex.

The Oyster Perpetual

In 1931, following the success of the first Oyster case—which was sealed against humidity and dust—Rolex achieved another milestone with the introduction of the Oyster Perpetual. The Caliber 620 (also known as the N/A) featured an automatic mechanism that differed from Harwood’s in that its central self-winding rotor made full, uninterrupted rotations. This movement used a bulky, complex gear stack positioned atop the barrel to transfer energy from the rotor to the mainspring. Like Harwood’s, the early Rolex movements wound the watch in only one direction.

Rolex introduced the Oyster Perpetual in 1931. The Caliber 620 was the first movement with a rotor that was not restricted and could oscillate a full 360 degrees

Winding Whichever Way

Most modern automatic watches wind in both directions They achieve this through what might seem like the dark arts—by way of a mystical mechanical marvel known as a ‘reverser.’ As the rotor makes its rounds, the reverser causes the mainspring to be wound regardless of the direction in which the rotor is travelling. This can be accomplished in several ways, the most common of which are a wheel-and-pinion coupling and a pawl lever.

Wheel and Pinion Coupling

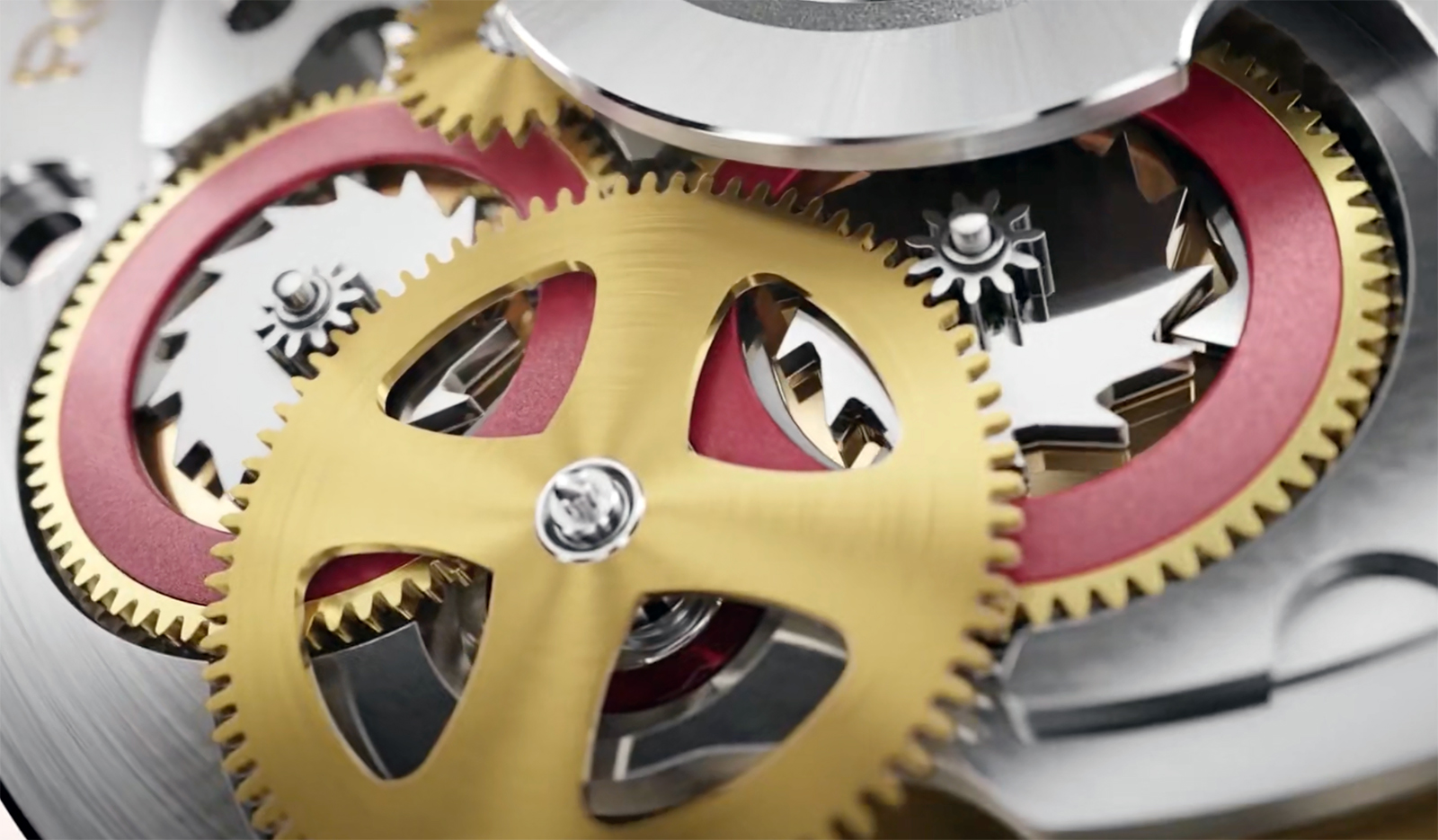

In 1950, Rolex launched the Caliber 1030, featuring a centrally mounted rotor with an updated automatic winding system. Instead of a complicated gear stack on top of the ratchet wheel, Rolex introduced a double wheel-and-pinion coupling into its automatic mechanism. Rolex refers to these as ‘reversing wheels.’

Diagram from the original patent. The oscillating mass (1) is dependent on a pinion (2) meshing with a reverser wheel (3) which drives reverser wheel (4). The reverser wheels (3 & 4) drive their respective ratchets (6 & 8), by a pawl coupling (5 & 7) which ensures each wheel rotates in a fixed direction.

You have likely seen them—Rolex’s now-famous ‘red wheels,’ which have been in use since 1952 and are still used today. For clarity, we will use a modern Rolex wheel-and-pinion coupling (reversing wheel) to explain how these work, while noting that variations exist across different watch movements.

The wheel-and-pinion coupling consists of three main parts: the wheel, which has teeth on the outside; the pinion, which has two sets of teeth; and the pawls, which have hooks on both ends. Together, these components form the ‘reversing wheel.’

With wheel-and-pinion couplings arranged in series, Rolex was able to achieve winding in both directions, a significant advancement at the time.

The rotor has a toothed pinion attached, which is responsible for transferring its power. This pinion meshes with the teeth of the first wheel of the wheel-and-pinion coupling, which in turn meshes with the second. When the rotor spins, these wheels are forced into motion. However, when two wheels in motion sit next to each other, they end up travelling in opposite directions. This is problematic because a mainspring can only be wound in one direction. This is where the pinions come into play.

When the rotor travels in a specific direction, the pinion inside the first wheel is locked by the pawls and forced to move in the same direction as its wheel. This causes the pinion to turn an auxiliary wheel, which winds the mainspring. The pinion inside reversing wheel number two isn’t locked, and the wheel and pinion travel in opposite directions, not contributing to winding as the pawl hooks glide over the teeth, waiting their turn to engage. When the rotor changes direction, the opposite wheel-and-pinion coupling engages. As a result, the mainspring is wound regardless of the rotor’s direction of travel.

Notably, some automatic mechanisms incorporate a stacked wheel-and-pinion coupling into a single wheel, allowing it to wind bidirectionally.

The wheel-and-pinion coupling is a highly successful system and the primary style in use today, though it is not without faults. These systems are complex, and the requirements for these wheels are stringent, as they perform significant work. Meticulous lubrication is also essential for proper functioning.

The Pawl Lever

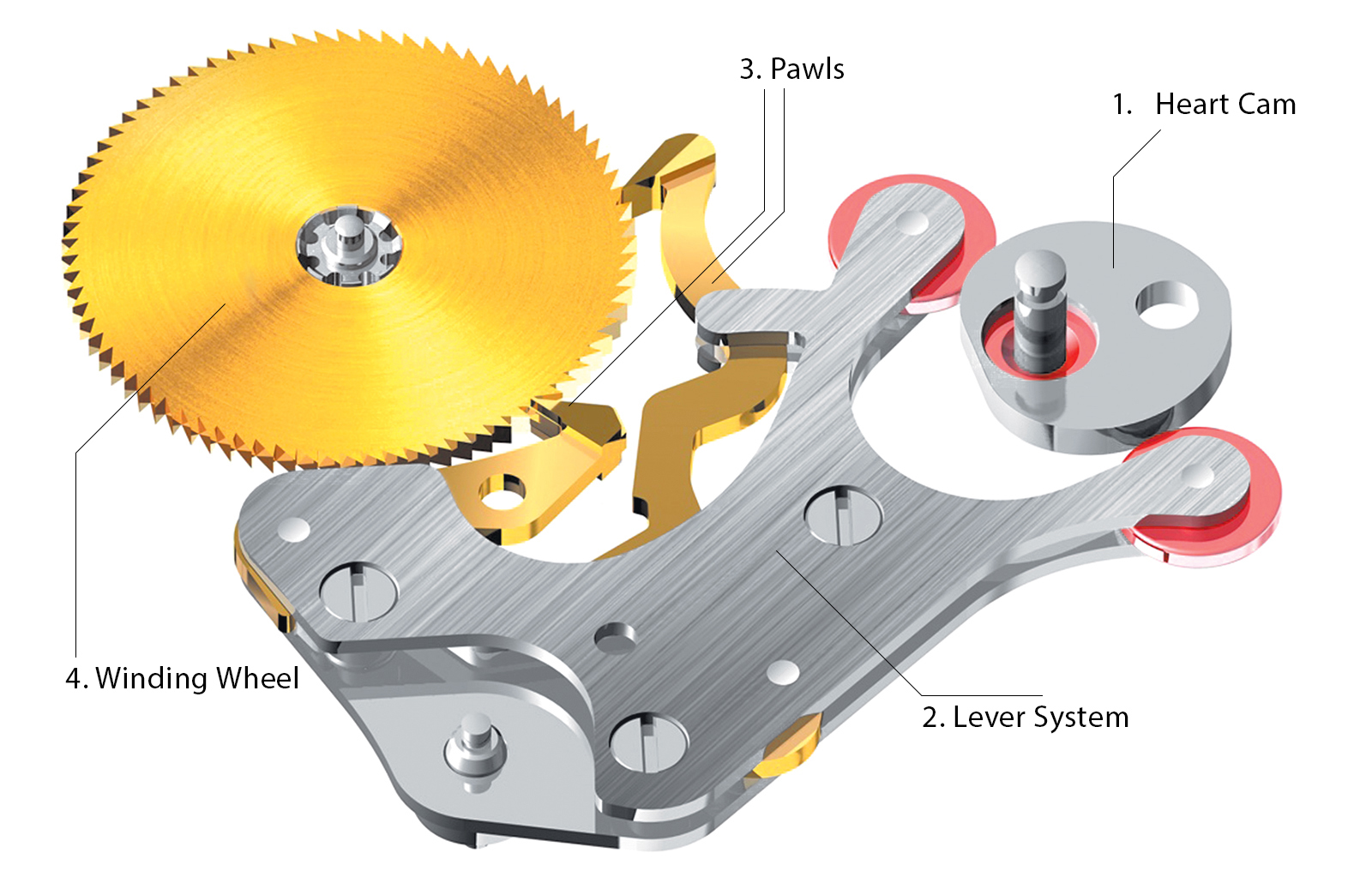

The pawl lever system for automatic winding is both simple and effective. It uses a centrally mounted self-winding rotor but has a much smaller train of wheels than a wheel-and-pinion coupling. It can operate with just one—the winding wheel—assisted by the magic of the pawl lever.

Essentially, a pawl lever has two ‘arms’ with hooks at their ends, which it uses to either ‘push’ or ‘pull’ the teeth of the winding wheel, thereby forcing it into rotation and winding the mainspring.

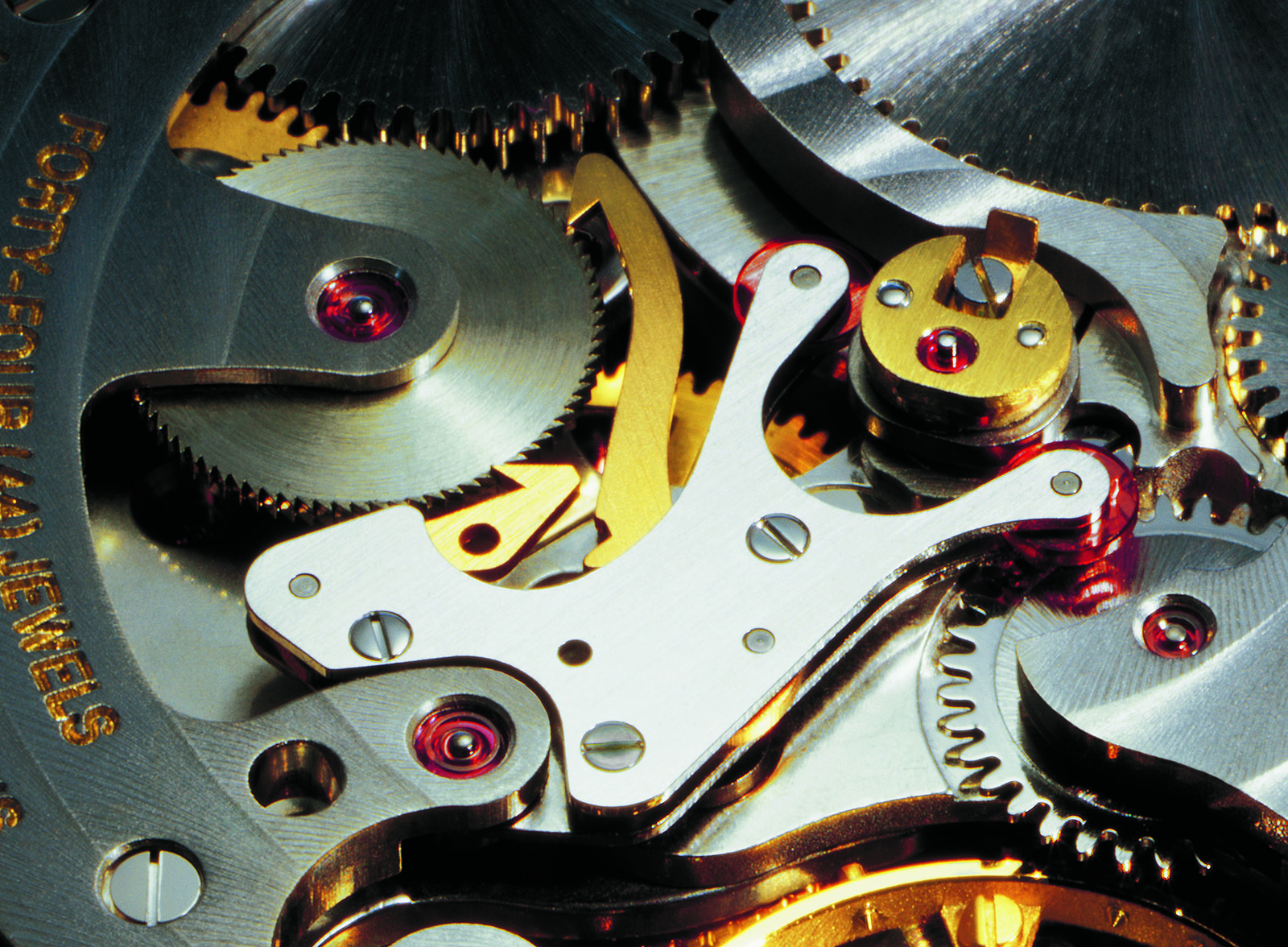

IWC’s Pellaton

IWC was the first to adopt the pawl lever in 1950, after Albert Pellaton, then the technical director of IWC, had spent several years developing the system. At the centre of the self-winding rotor is a fixed, heart-shaped cam (1). The pawl lever (2) straddles the heart cam, and as the rotor spins, the eccentricity of the cam forces the pawl arms (3) to rock back and forth.

When the rotor spins clockwise, the hook on the end of arm number one ‘grabs’ a tooth and pulls the winding wheel (4) backward, while the tip of arm number two glides over the teeth, not contributing to the wheel’s rotation. As the rotor travels counterclockwise, the arms switch roles. With each pull of a tooth, the mainspring winds a little tighter.

Seiko ‘Magic’

Seiko released its first automatic movement in 1956, but 1959 marked an automatic revolution. That year, Seiko introduced the Gyro Marvel, its first watch to feature the Magic Lever system. The Magic Lever is a pawl lever based on IWC’s Pellaton winding, distinguished by its simplicity. Seiko simplified the pawl lever further by placing it directly on the rotor. Similar in construction to a wishbone, it attaches to an offset pin at the centre of the rotor. As the rotor spins, the arms of the pawl lever rock back and forth.

The Magic Lever is a simple yet ingenious bidirectional winding system that maximises efficiency with minimal components

When the rotor travels in one direction, one arm pulls the winding wheel backward, much like the Pellaton system, while the tips of the second arm glide over the teeth. The key difference occurs when the rotor travels in the opposite direction, as arm number two now pushes the winding wheel forward instead of pulling it back, resulting in a simpler system. With just three components, the watch can be automatically wound—truly magical.

It is an elegantly simple system with few potential failure points. In fact, it was so efficient that Seiko largely dispensed with the manual winding feature in its watches, opting for the automatic mechanism as the sole means of operation, as a minute or so of shaking is enough to prepare it for wear.

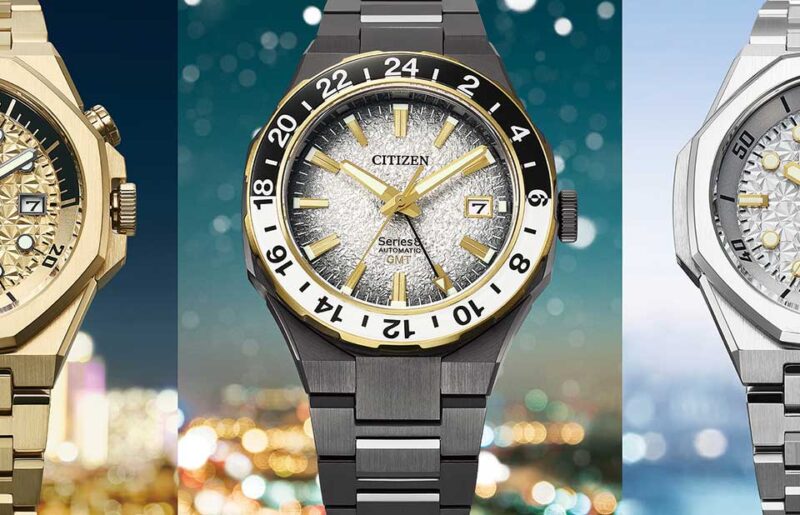

One Way Winding

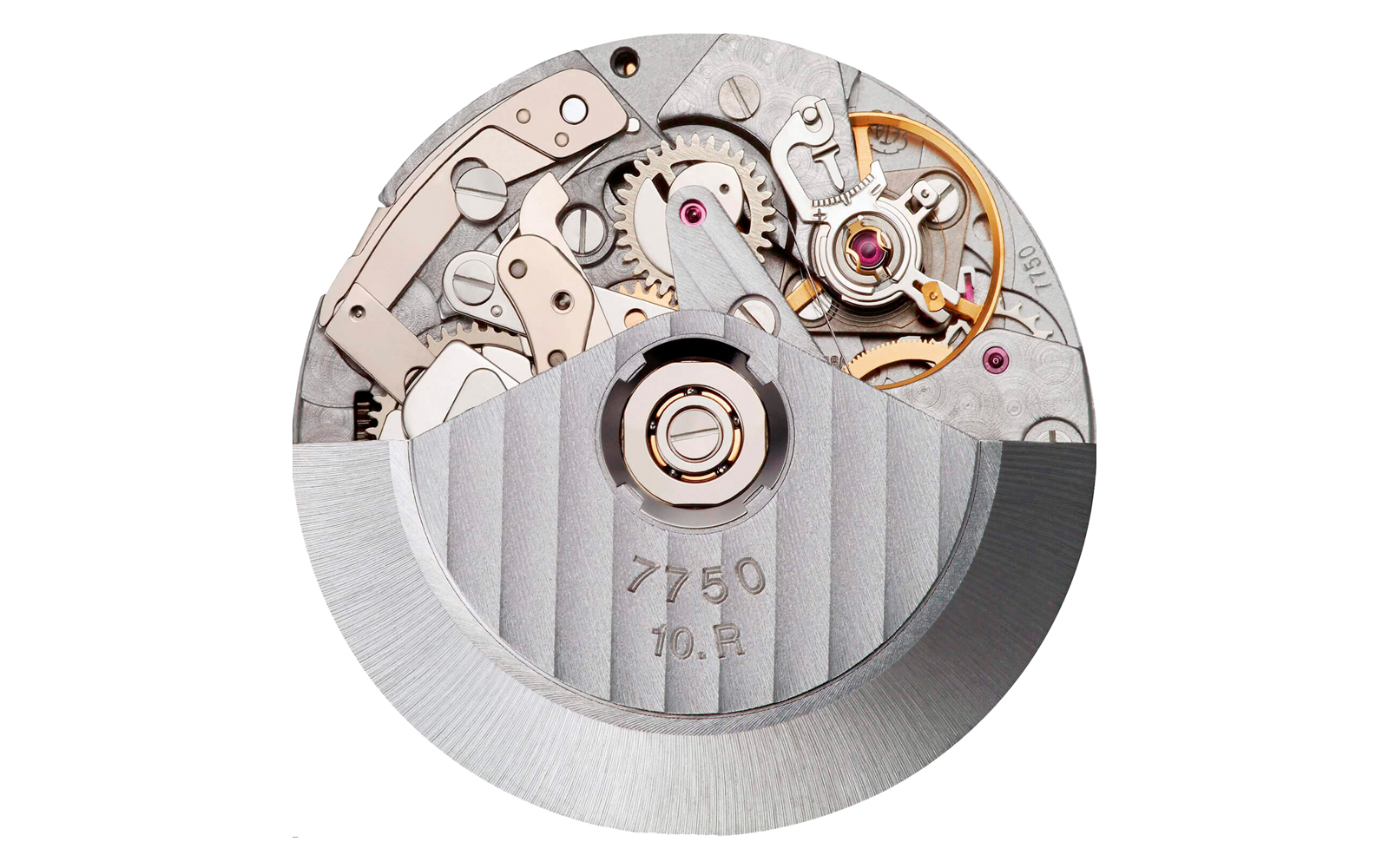

It is easy to assume that bidirectional winding is far superior to unidirectional winding, but that is not necessarily the case. Numerous tests on unidirectional winding have demonstrated its advantages. Results indicate that in a regularly worn watch, the mainspring is typically fully wound, demonstrating that unidirectional winding is sufficient to keep the watch running. This underscores the point that more does not always mean better. The ETA 7750 employs a single wheel-and-pinion coupling and winds in only one direction. I have yet to meet an ETA 7750-powered watch owner who complains about the need for manual winding to keep it running.

The Heavy Weight Champion

Self-winding rotors are typically made from heavy metals, with brass, gold, platinum, and tungsten carbide being used. The most common style today is a centrally mounted rotor roughly half the size of the movement, though other designs are also used.

The Eccentric Self-Winding Weight

The eccentric self-winding weight is small and offset, unlike the half-movement rotor. Famously used by Universal Genève, Patek Philippe, and Heuer in the Calibres 11 and 12, this design is commonly referred to as a micro-rotor.

This rotor is compact, usually measuring less than a quarter of the movement’s size. A metal heavier than brass is generally used for these, as their smaller footprint compared to a half-movement rotor requires additional weight for gravity and inertia to wind the spring. Due to the density of the metals used, micro-rotors make for highly efficient self-winding mechanisms. The primary advantage of a micro-rotor is a thinner movement, as it eliminates the need for a large automatic mechanism on top.

Peripheral Vision

The peripheral self-winding rotor sits along the outer edge of the watch movement. As with other designs, a heavy mass is used to wind the mainspring, but in this case, it encircles the movement’s outer perimeter, allowing the entire mechanism to remain visible.

In recent years, Carl F. Bucherer has led advancements in this technology, while other companies have experimented with it. However, I do not foresee widespread adoption in the future. While the ability to view the entire movement is an appealing feature, its benefits do not appear to outweigh the complexity of the design.

In Carl F. Bucherer’s movements, the oscillating mass is made of tungsten and mounted on a ring. Beneath it sits another ring with internal teeth that mesh with the first gear (with a shock protection system) in the automatic winding train

The Vacheron Constantin Caliber 2160 features a gold peripheral rotor paired with a Magic Lever winding system.

Ball Bearing Vs Axle

Due to the self-winding rotor’s mass, wear and tear can be significant. Two primary methods allow the rotor to turn freely: ball bearings and an axle. Both methods are simple and effective. Traditionally, ball bearings were made of steel, but some brands are now experimenting with ceramic.

- Rolex 3135

- Rolex 3235

I previously stated that I preferred an axle over a ball-bearing system, but my opinion has since changed. After observing many more ball-bearing rotors, I now recognize that they endure years of use better than axle-based systems.

Final Thoughts

Determining whether one system is superior to another is tough, but let’s give it a shot. Having worked on various automatic systems, I have found that each has its advantages and drawbacks. That said, the Seiko Magic Lever, combined with a ball-bearing self-winding rotor, has consistently proven to be a reliable and effective combination for decades.

The wheel-and-pinion coupling remains a favourite in the industry, widely used by many brands—some executing it more effectively than others. Rolex deserves recognition here, as its reversing wheels are remarkably durable, rarely encountering issues and withstanding years of wear better than other types.

In some ways, we have come a long way since the first modern automatic watch debuted at the Basel Fair in 1926, but in other ways, we have not come all that far. Automatic systems are largely the same, albeit more refined, which reflects much of what defines watchmaking. To me, that is where the magic of horology lies. We are merely improving, not reinventing, as our horological forefathers invented some seriously impressive stuff.